So I’m refurbishing the Mac Classic II I got in 2016 now that I’ve found that BlueSCSI is a fairly cheap way of providing large replacement storage. The 40 MB (yes, 40 MB) drive from 1992 can finally be replaced.

Hit a snag, though: DiskCopy won’t copy a disk with errors, which this drive seemed to have. DiskCopy also won’t repair the boot disk, so you have to find a bootable floppy or some other way to work around this limitation. The only readily available bootable disk image I could find was the System 7.1 Disk Tools floppy — which reported no errors on my drive! Later versions of Disk First Aid would fix it, but weren’t provided on a bootable image.

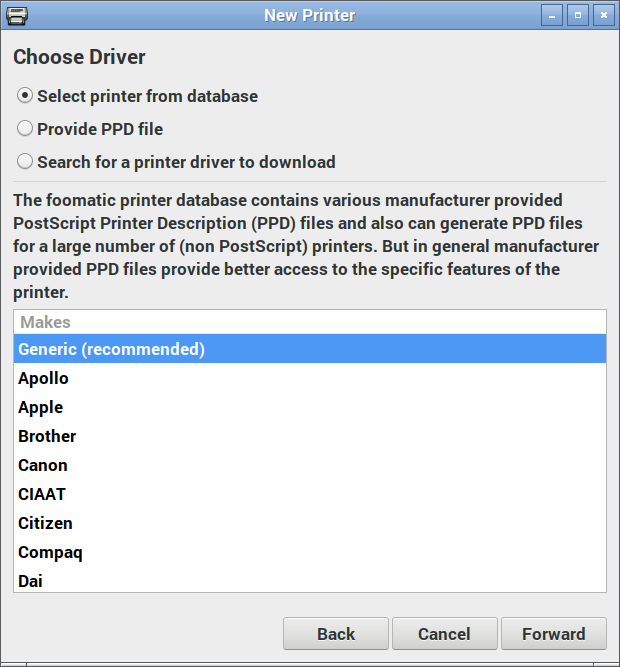

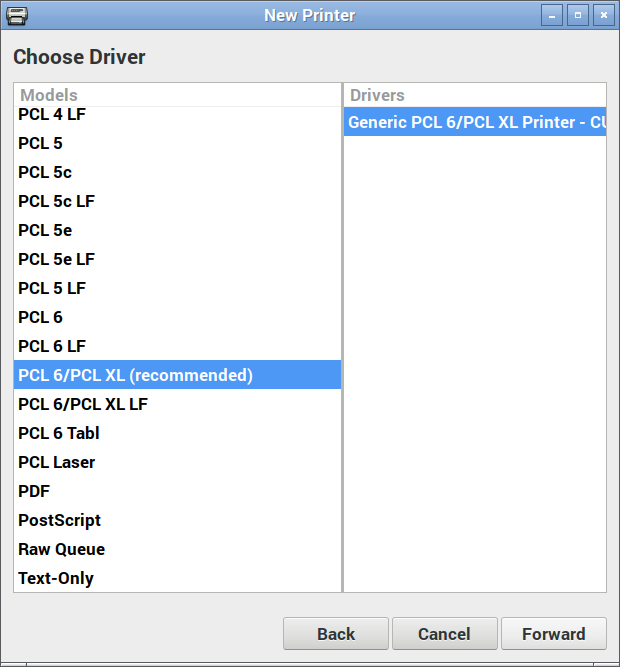

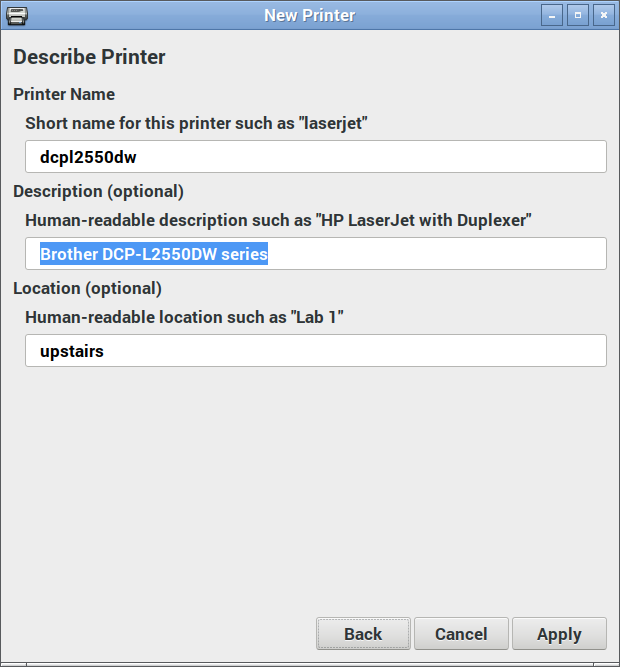

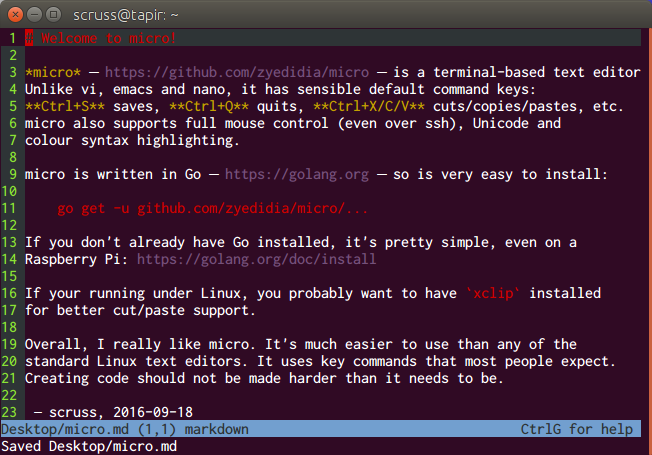

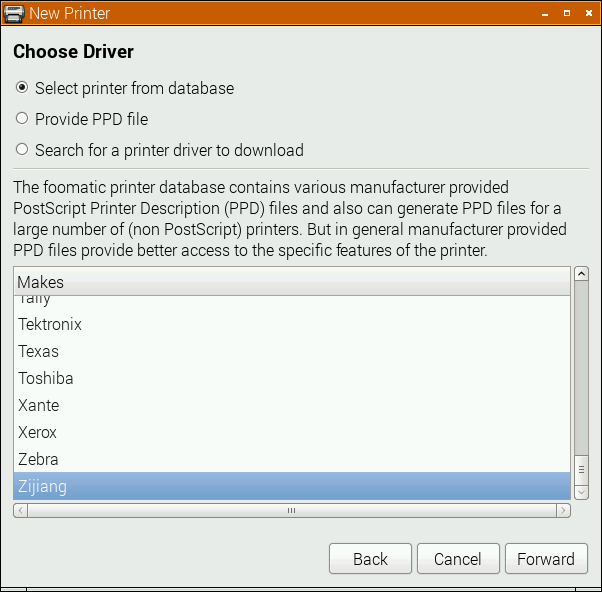

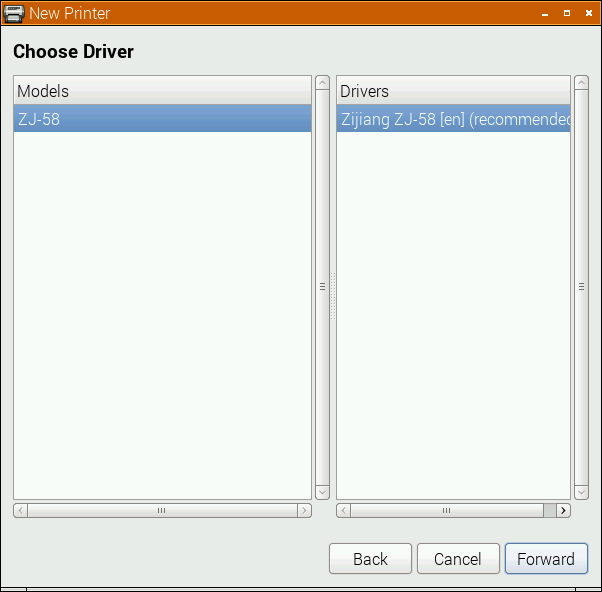

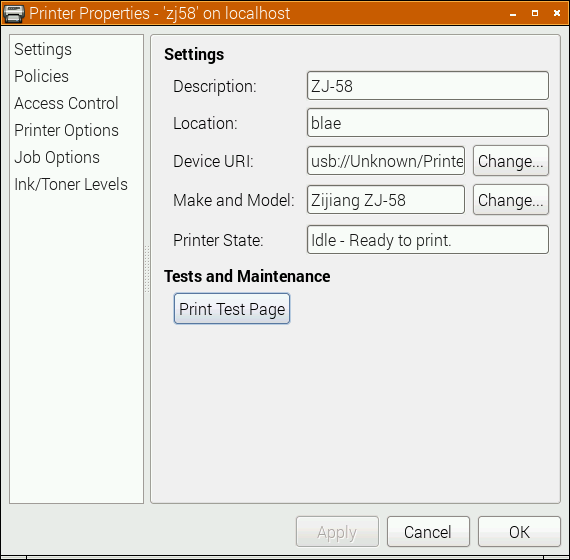

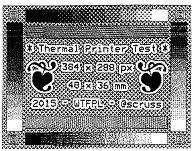

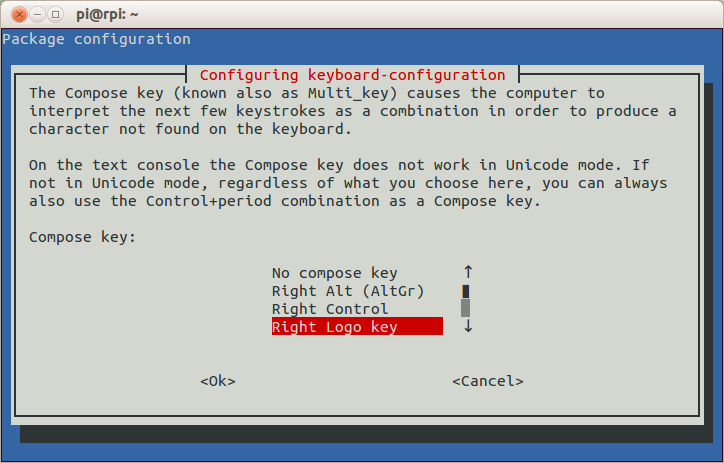

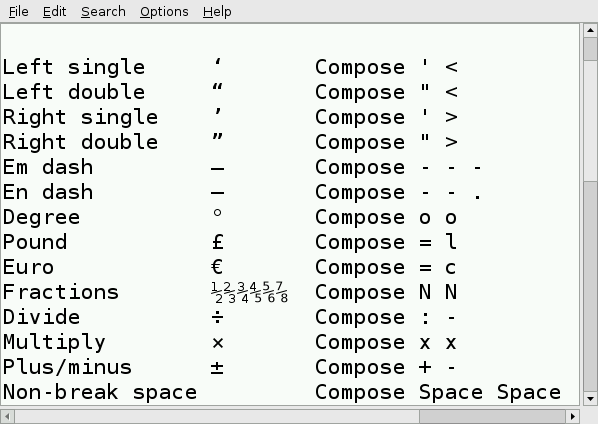

Here’s the 7.1 Disk Tools floppy with all of the apps replaced by Disk First Aid 7.2. Both of these were found on the Internet Archive’s download.info.apple.com mirror and combined:

Disk duly repaired, DiskCopy was happy, backup complete. Eventually: the Classic II is not a fast machine at all.

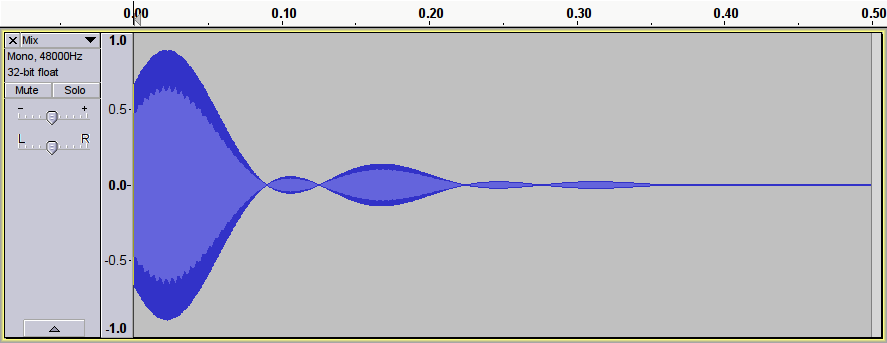

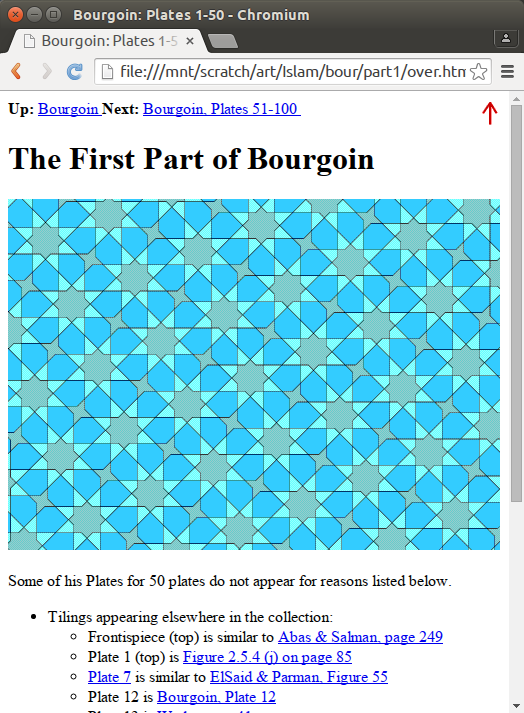

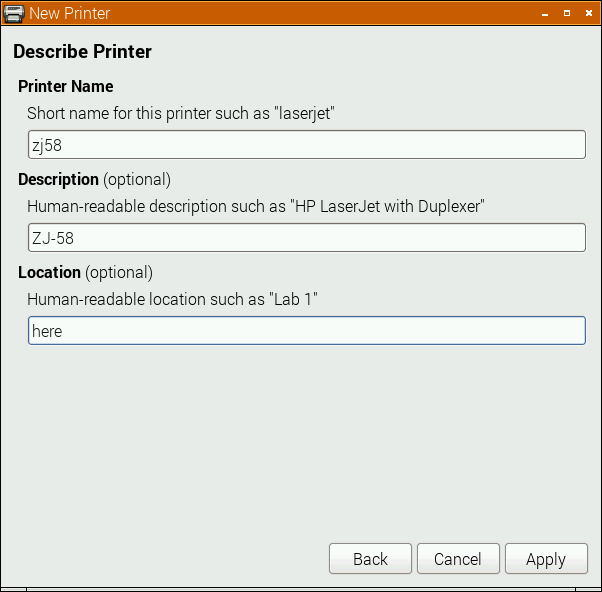

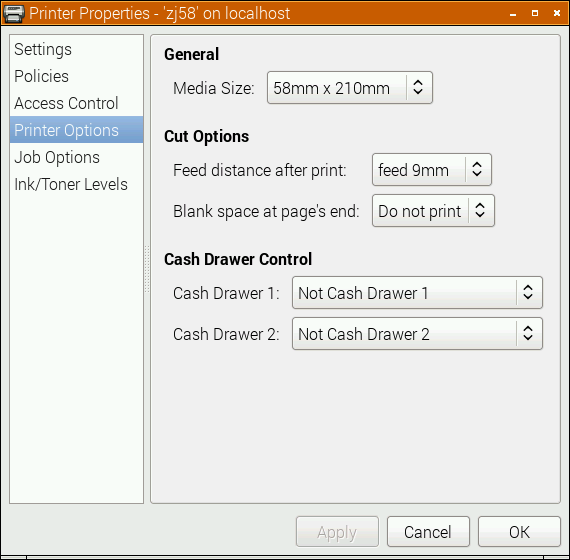

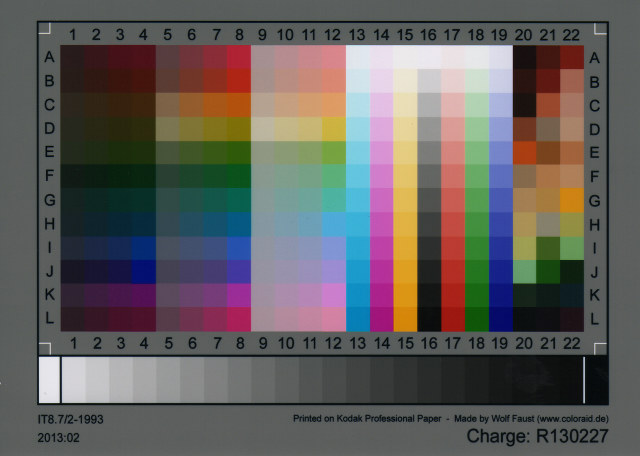

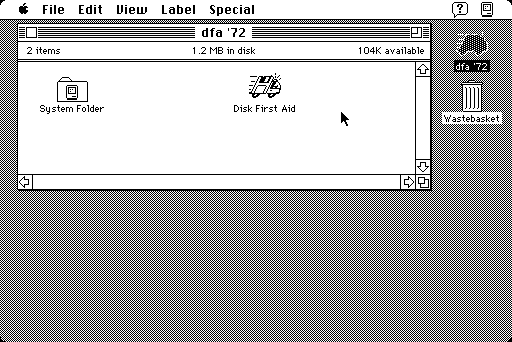

I love the old Mac icons, how they packed so much into so few pixels:

It’s a stylized ambulance with flashing light and driver, the side is a floppy disk, it’s got motion lines and the whole icon is slanted to indicate speed/rush. Nice!

Vaguely related: most old Mac software is stored as Stuffit! archives. These don’t really work too well on other systems, as they use a compression scheme all their own and are specialized to handle the forked filesystem that old Macs use. Most emulators won’t know what to do with them unless you jump through hoops in the transfer stage.

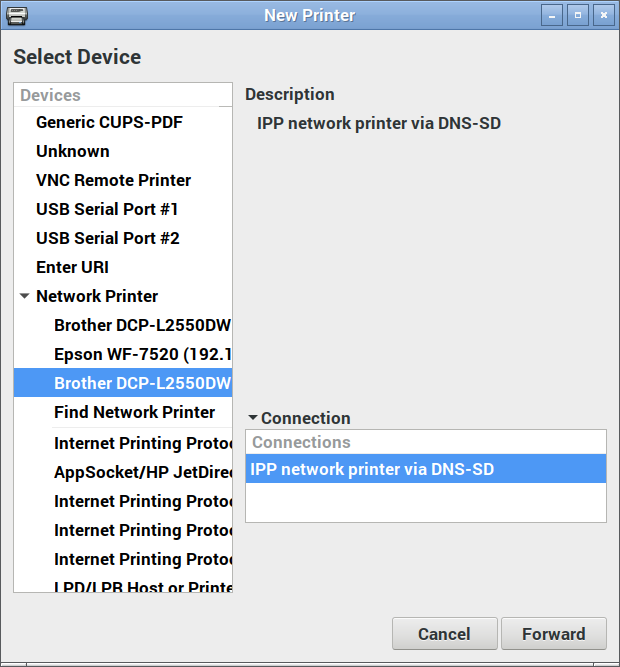

Fortunately, the ancient Linux package hfsutils knows the ways of these hoops, if only you tell it when to jump. The script below takes a Stuffit! file as its sole argument, and creates a slightly larger HFS image containing the archive, with all the attributes set for Stuffit! Expander or what-have-you to unpack it.

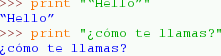

#!/bin/bash

# sitdsk - make an HFS image containing a properly typed sit file

# requires hfsutils

# scruss, 2021-07

if

[ $# -ne 1 ]

then

echo Usage: $0 file.sit

exit 1

fi

base="${1%.sit}"

# hformat won't touch anything smaller than 800 KB,

# so min image size will be 800 * 1.25 = 1000 KB

size=$(du -k "$1" | awk '{print ($1 >= 800)?$1:800}')

dsk="${base}.dsk"

dd status=none of="$dsk" if=/dev/zero bs=1K count=$((size * 125 / 100))

hformat -l "$base" "$dsk"

# note that hformat does an implicit 'hmount'

hcopy "$1" ':'

# and hcopy silently changes underscores to spaces

hattrib -t 'SIT!' -c 'SITx' ":$(echo ${1} | tr '_' ' ')"

hls -l

humount

What this does:

- creates a blank image file roughly 25% larger than the archive (or 1000 KB, whichever is the larger) using dd;

- ‘formats’ the image file with an HFS filesystem using hformat;

- copies the archive to the image using hcopy;

- attempts to set the file type and creator using hattrib;

- lists the archive contents using hls;

- disconnects/unmounts the image from the hfsutils system using humount.

Notice I said it “attempts” to set the file type. hfsutils does some file renaming on the fly, and all I know about is that it changes underscores to spaces. So if there are other changes made by hfsutils, this step may fail. The package also gets really confused by images smaller than 800 KB, so small archives are rounded up in size to keep hformat happy.