We were visited by four small raccoons this morning, who decided to practice their judo moves on the back deck.

work as if you live in the early days of a better nation

Exhibit A:

also known as “Monster BASICS Sound reactive RGB+IC Color Flow LED strip”. It’s $5 or so at Dollarama, and includes a USB cable for power and a remote control. It’s two metres long and includes 60 RGB LEDs. Are these really super-cheap NeoPixel clones?

I’m going to keep the USB power so I can power it from a power bank, but otherwise convert it to a string of smart LEDs. We lose the remote control capability.

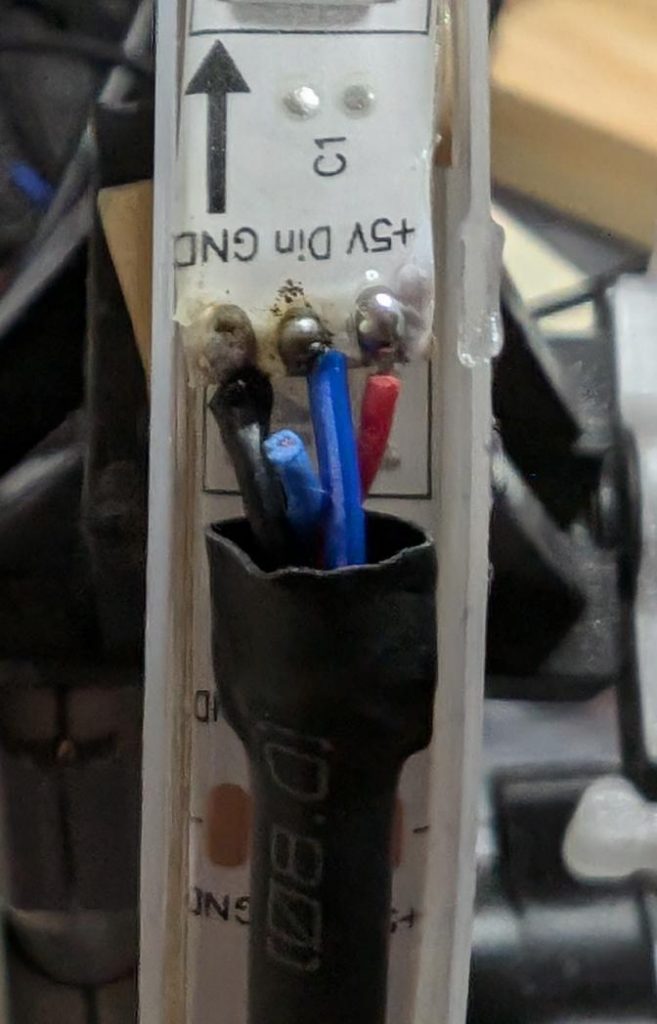

Pull back the heatshrink at the USB end:

… and there are our connectors. We want to disconnect the blue Din (Data In) line from the built in controller, and solder new wires to Din and GND to run from a microcontroller board.

Maybe not the best solder job, but there are new wires feeding through the heatshrink and soldered onto the strip.

Here’s the heatshrink pushed back, and everything secured with a cable tie.

Now to feed it from standard MicroPython NeoPixel code, suitably jazzed up for 60 pixels.

A pretty decent result for $5!

So you bought that Brother laser printer like everyone told you to. And now it’s out of toner, so you replaced the cartridge. If you were in the USA, you could return the cartridge for free using the included label. But in Canada … it’s a whole deal including registering with Brother and giving away your contact details and, and, and …

Anyway, my dear fellow Canadians, I went through the process and downloaded the label PDF so you don’t have to:

If you have an address label printer, I even cropped it for you (with only slight font corruption):

I’m pretty sure this is a generic label, since:

But if they do complain, you know what to do: brother.ca/en/environment

reference copy: Thousand Days: Concept on github.

Stewart Russell – scruss.com — 2024-03-26, at age 19999 days …

One’s thousand day(s) celebration occurs every thousand days of a person’s life. They are meant to be a recognition of getting this far, and are celebrated at the person’s own discretion.

1000 days is approximately:

4000 days is just shy of 11 years.

Compared to regular birthdays, thousand days:

My ancient Your 1000 Day Birthday Calculator, first published in 2002 and untouched since 2010.

So it turns out that GNU date can handle arbitrary date maths quite well. For example:

date --iso-8601=date --date="1996-11-09 + 10000 days"

returns 2024-03-27.

Excel or any other spreadsheet will do, too. Although not for too many years back

This is an idea for finding people who have a thousand day on the same day as you. I suggest using 1851-10-01 as a datum, because:

then calculate

( (birth_date - 1851-10-01) mod 1000 ) + 1

This results in a number 1 – 1000. Everyone with the same number shares a 1000 day birthday with you.

Why not 0 – 999?

There are more, but these were found from Wikipedia’s year pages

🅭 2024, Stewart Russell, scruss.com

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

There are no trademarks, patents, official websites, social media or official anythings attached to this concept. Please take the idea and do good with it.

I’ve had this idea kicking around my head for at least the last 20 years. For $REASONS, it turns out I’m not very good at implementing stuff. I’d far rather someone else took this idea and ran with it than let it sit undeveloped.

It’s mid-February in Toronto: -10 °C and snowy. The memory of chirping summer fields is dim. But in my heart there is always a cricket-loud meadow.

Short of moving somewhere warmer, I’m going to have to make my own midwinter crickets. I have micro-controllers and tiny speakers: how hard can this be?

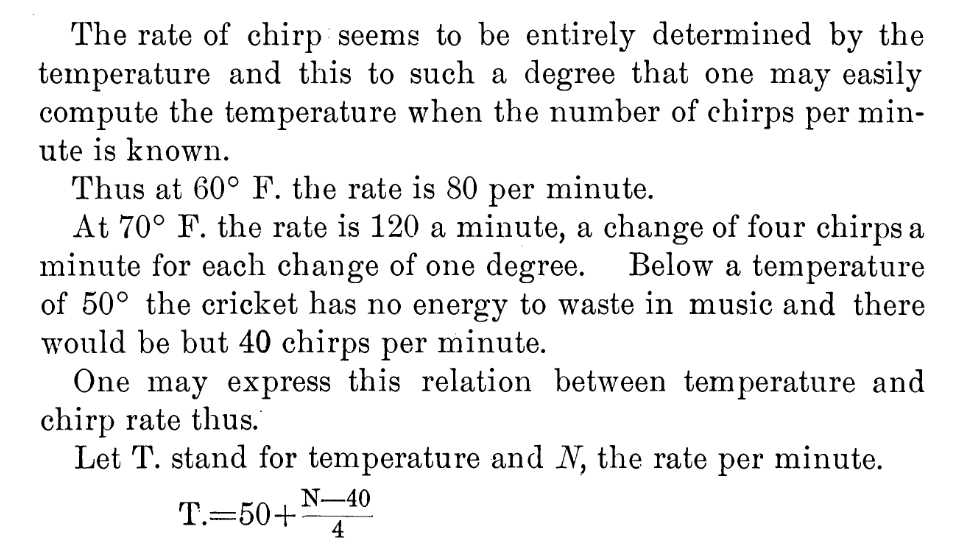

I could have merely made these beep away at a fixed rate, but I know that real crickets tend to chirp faster as the day grows warmer. This relationship is frequently referred to as Dolbear’s law. The American inventor Amos Dolbear published his observation (without data or species identification) in The American Naturalist in 1897: The Cricket as a Thermometer —

When emulating crickets I’m less interested in the rate of chirps per minute, but rather in the period between chirps. I could also care entirely less about barbarian units, so I reformulated it in °C (t) and milliseconds (p):

t = ⅑ × (40 + 75000 ÷ p)

Since I know that the micro-controller has an internal temperature sensor, I’m particularly interested in the inverse relationship:

p = 15000 ÷ (9 * t ÷ 5 – 8)

I can check this against one of Dolbear’s observations for 70°F (= 21⅑ °C, or 190/9) and 120 chirps / minute (= 2 Hz, or a period of 500 ms):

p = 15000 ÷ (9 * t ÷ 5 – 8)

= 15000 ÷ (9 * (190 ÷ 9) ÷ 5 – 8)

= 15000 ÷ (190 ÷ 5 – 8)

= 15000 ÷ 30

= 500

Now I’ve got the timing worked out, how about the chirp sound. From a couple of recordings of cricket meadows I’ve made over the years, I observed:

I didn’t attempt to model the actual stridulating mechanism of a particular species of cricket. I made what sounded sort of right to me. Hey, if Amos Dolbear could make stuff up and get it accepted as a “law”, I can at least get away with pulse width modulation and tiny tinny speakers …

This is the profile I came up with:

That’s a total of 126 ms, or ⅛ish seconds. In the code I made each instance play at a randomly-selected relative pitch of ±200 Hz on the above numbers.

For the speaker, I have a bunch of cheap PC motherboard beepers. They have a Dupont header that spans four pins on a Raspberry Pi Pico header, so if you put one on the ground pin at pin 23, the output will be connected to pin 26, aka GPIO 20:

So — finally — here’s the MicroPython code:

# cricket thermometer simulator - scruss, 2024-02

# uses a buzzer on GPIO 20 to make cricket(ish) noises

# MicroPython - for Raspberry Pi Pico

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

from machine import Pin, PWM, ADC, freq

from time import sleep_ms, ticks_ms, ticks_diff

from random import seed, randrange

freq(125000000) # use default CPU freq

seed() # start with a truly random seed

pwm_out = PWM(Pin(20), freq=10, duty_u16=0) # can't do freq=0

led = Pin("LED", Pin.OUT)

sensor_temp = machine.ADC(4) # adc channel for internal temperature

TOO_COLD = 10.0 # crickets don't chirp below 10 °C (allegedly)

temps = [] # for smoothing out temperature sensor noise

personal_freq_delta = randrange(400) - 199 # different pitch every time

chirp_data = [

# cadence, duty_u16, freq

# there is a cadence=1 silence after each of these

[3, 16384, 4568 + personal_freq_delta],

[4, 32768, 4824 + personal_freq_delta],

[4, 32768, 4824 + personal_freq_delta],

[3, 16384, 4568 + personal_freq_delta],

]

cadence_ms = 7 # length multiplier for playback

def chirp_period_ms(t_c):

# for a given temperature t_c (in °C), returns the

# estimated cricket chirp period in milliseconds.

#

# Based on

# Dolbear, Amos (1897). "The cricket as a thermometer".

# The American Naturalist. 31 (371): 970–971. doi:10.1086/276739

#

# The inverse function is:

# t_c = (75000 / chirp_period_ms + 40) / 9

return int(15000 / (9 * t_c / 5 - 8))

def internal_temperature(temp_adc):

# see pico-micropython-examples / adc / temperature.py

return (

27

- ((temp_adc.read_u16() * (3.3 / (65535))) - 0.706) / 0.001721

)

def chirp(pwm_channel):

for peep in chirp_data:

pwm_channel.freq(peep[2])

pwm_channel.duty_u16(peep[1])

sleep_ms(cadence_ms * peep[0])

# short silence

pwm_channel.duty_u16(0)

pwm_channel.freq(10)

sleep_ms(cadence_ms)

led.value(0) # led off at start; blinks if chirping

### Start: pause a random amount (less than 2 s) before starting

sleep_ms(randrange(2000))

while True:

loop_start_ms = ticks_ms()

sleep_ms(5) # tiny delay to stop the main loop from thrashing

temps.append(internal_temperature(sensor_temp))

if len(temps) > 5:

temps = temps[1:]

avg_temp = sum(temps) / len(temps)

if avg_temp >= TOO_COLD:

led.value(1)

loop_period_ms = chirp_period_ms(avg_temp)

chirp(pwm_out)

led.value(0)

loop_elapsed_ms = ticks_diff(ticks_ms(), loop_start_ms)

sleep_ms(loop_period_ms - loop_elapsed_ms)

There are a few more details in the code that I haven’t covered here:

Before I show you the next video, I need to say: no real crickets were harmed in the making of this post. I took the bucket outside (roughly -5 °C) and the “crickets” stopped chirping as they cooled down. Don’t worry, they started back up chirping again when I took them inside.

If you really must try this on your on Amstrad CPC:

(this is an old post from 2021 that got caught in my drafts somehow)

Mike asked:

To which I suggested:

Not very helpful links, more of a thought-dump:

First PostScript font: STSong (华文宋体) was released in 1991, making it the first PostScript font by a Chinese foundry [ref: Typekit blog — Pan-CJK Partner Profile: SinoType]. But STSong looks like Garamond(ish).

![A table of the latin characters @, A-Z, [, \, ], ^, _, `, a-z and { in STSong half-width latin, taken from fontforge](https://scruss.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Screenshot-from-2024-01-07-11-44-09.png)

Maybe source: GB 5007.1-85 24×24 Bitmap Font Set of Chinese Characters for Information Exchange. Originally from 1985, this is a more recent version: GB 5007.1-2010: Information technology—Chinese ideogram coded character set (basic set)—24 dot matrix font.

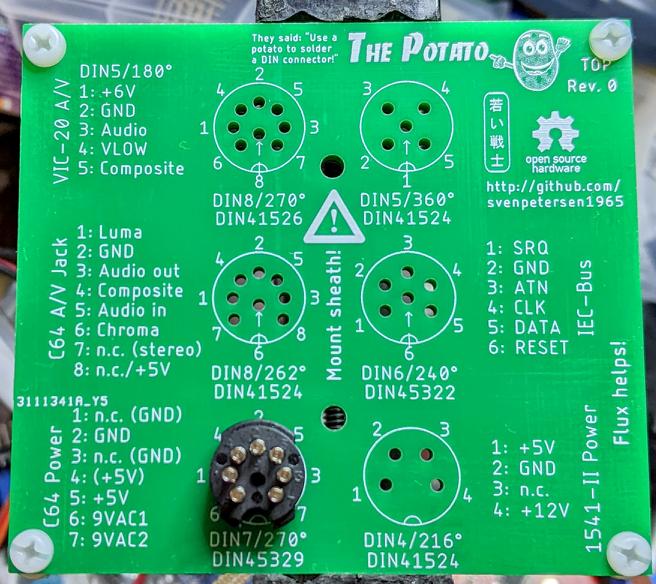

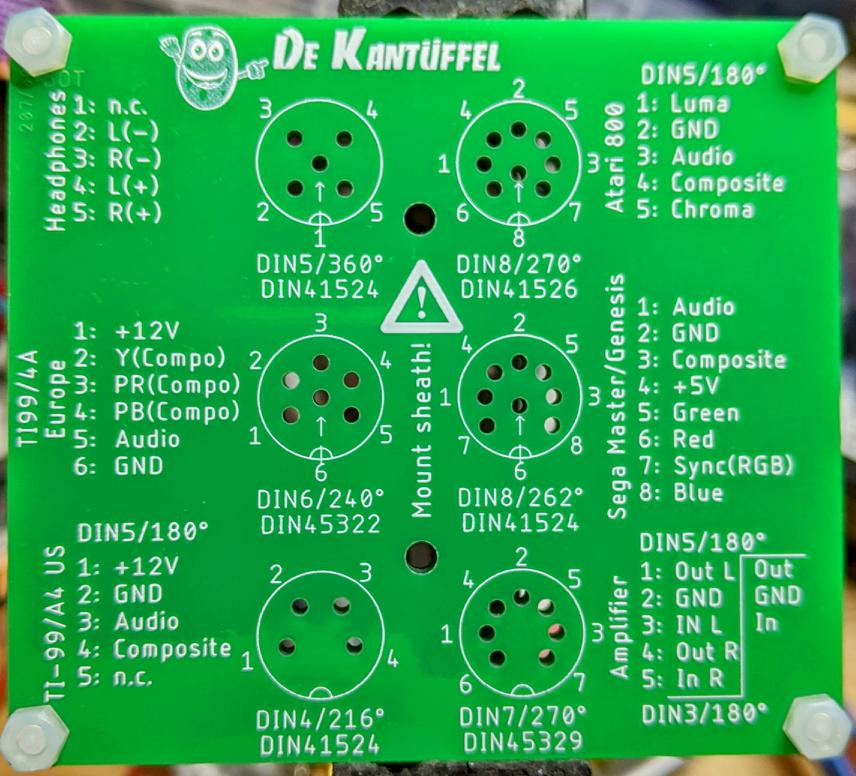

… is a thing to help soldering DIN connectors. I had some made at JLCPCB, and will have them for sale at World of Commodore tomorrow.

You can get the source from svenpetersen1965/DIN-connector_soldering-aid-The-Potato. I had the file Rev. 0/Gerber /gerber_The_Potato_noFrame_v0a.zip made, and it seems to fit connector pins well.

Each Potato is made up of two PCBs, spaced apart by a nylon washer and held together by M3 nylon screws.

This is a mini celebratory post to say that I’ve fixed the database encoding problems on this blog. It looks like I will have to go through the posts manually to correct the errors still, but at least I can enter, store and display UTF-8 characters as expected.

“? µ ° × — – ½ ¾ £ é?êè”, he said with some relief.

Postmortem: For reasons I cannot explain or remember, the database on this blog flipped to an archaic character set: latin1, aka ISO/IEC 8859-1. A partial fix was effected by downloading the entire site’s database backup, and changing all the following references in the SQL:

For additional annoyance, the entire SQL dump was too big to load back into phpmyadmin, so I had to split it by table. Thank goodness for awk!

#!/usr/bin/awk -f

BEGIN {

outfile = "nothing.sql";

}

/^# Table: / {

# very special comment in WP backup that introduces a new table

# last field is table_name,

# which we use to create table_name.sql

t = $NF

gsub(/`/, "", t);

outfile = t ".sql";

}

{

print > outfile;

}

The data still appears to be confused. For example, in the post Compose yourself, Raspberry Pi!, what should appear as “That little key marked “Compose”” appears as “That little key marked “Composeâ€Â”. This isn’t a straight conversion of one character set to another. It appears to have been double-encoded, and wrongly too.

Still, at least I can now write again and have whatever new things I make turn up the way I like. Editing 20 years of blog posts awaits … zzz

My OpenProcessing demo “autumn in canada”, redone as a NAPLPS playback file. Yes, it would have been nice to have outlined leaves, but I’ve only got four colours to play with that are vaguely autumnal in NAPLPS’s limited 2-bit RGB.

Played back via dosbox and PP3, with help from John Durno‘s very useful Displaying NAPLPS Graphics on a Modern Computer: Technical Note.

This file only displays 64 leaves, as more leaves caused the emulated Commodore 64 NAPLPS viewer I was running to crash.

NAPLPS — an almost-forgotten videotex vector graphics format with a regrettable pronunciation (/nap-lips/, no really) — was really hard to create. Back in the early days when it was a worthwhile Canadian initiative called Telidon (see Inter/Access’s exhibit Remember Tomorrow: A Telidon Story) it required a custom video workstation costing $$$$$$. It got cheaper by the time the 1990s rolled round, but it was never easy and so interest waned.

I don’t claim what I made is particularly interesting:

but even decoding the tutorial and standards material was hard. NAPLPS made heavy use of bitfields interleaved and packed into 7 and 8-bit characters. It was kind of a clever idea (lower resolution data could be packed into fewer bytes) but the implementation is quite unpleasant.

A few of the references/tools/resources I relied on:

Here’s the fragment of code I wrote to generate the NAPLPS:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

# draw a disappointing maple leaf in NAPLPS - scruss, 2023-09

# stylized maple leaf polygon, quite similar to

# the coordinates used in the Canadian flag ...

maple = [

[62, 2],

[62, 35],

[94, 31],

[91, 41],

[122, 66],

[113, 70],

[119, 90],

[100, 86],

[97, 96],

[77, 74],

[85, 114],

[73, 108],

[62, 130],

[51, 108],

[39, 114],

[47, 74],

[27, 96],

[24, 86],

[5, 90],

[11, 70],

[2, 66],

[33, 41],

[30, 31],

[62, 35],

]

def colour(r, g, b):

# r, g and b are limited to the range 0-3

return chr(0o74) + chr(

64

+ ((g & 2) << 4)

+ ((r & 2) << 3)

+ ((b & 2) << 2)

+ ((g & 1) << 2)

+ ((r & 1) << 1)

+ (b & 1)

)

def coord(x, y):

# if you stick with 256 x 192 integer coordinates this should be okay

xsign = 0

ysign = 0

if x < 0:

xsign = 1

x = x * -1

x = ((x ^ 255) + 1) & 255

if y < 0:

ysign = 1

y = y * -1

y = ((y ^ 255) + 1) & 255

return (

chr(

64

+ (xsign << 5)

+ ((x & 0xC0) >> 3)

+ (ysign << 2)

+ ((y & 0xC0) >> 6)

)

+ chr(64 + ((x & 0x38)) + ((y & 0x38) >> 3))

+ chr(64 + ((x & 7) << 3) + (y & 7))

)

f = open("maple.nap", "w")

f.write(chr(0x18) + chr(0x1B)) # preamble

f.write(chr(0o16)) # SO: into graphics mode

f.write(colour(0, 0, 0)) # black

f.write(chr(0o40) + chr(0o120)) # clear screen to current colour

f.write(colour(3, 0, 0)) # red

# *** STALK ***

f.write(

chr(0o44) + coord(maple[0][0], maple[0][1])

) # point set absolute

f.write(

chr(0o51)

+ coord(maple[1][0] - maple[0][0], maple[1][1] - maple[0][1])

) # line relative

# *** LEAF ***

f.write(

chr(0o67) + coord(maple[1][0], maple[1][1])

) # set polygon filled

# append all the relative leaf vertices

for i in range(2, len(maple)):

f.write(

coord(

maple[i][0] - maple[i - 1][0], maple[i][1] - maple[i - 1][1]

)

)

f.write(chr(0x0F) + chr(0x1A)) # postamble

f.close()

There are a couple of perhaps useful routines in there:

colour(r, g, b) spits out the code for two bits per component RGB. Inputs are limited to the range 0–3 without error checkingcoord(x, y) converts integer coordinates to a NAPLPS output stream. Best limited to a 256 × 192 size. Will also work with positive/negative relative coordinates.Here’s the generated file:

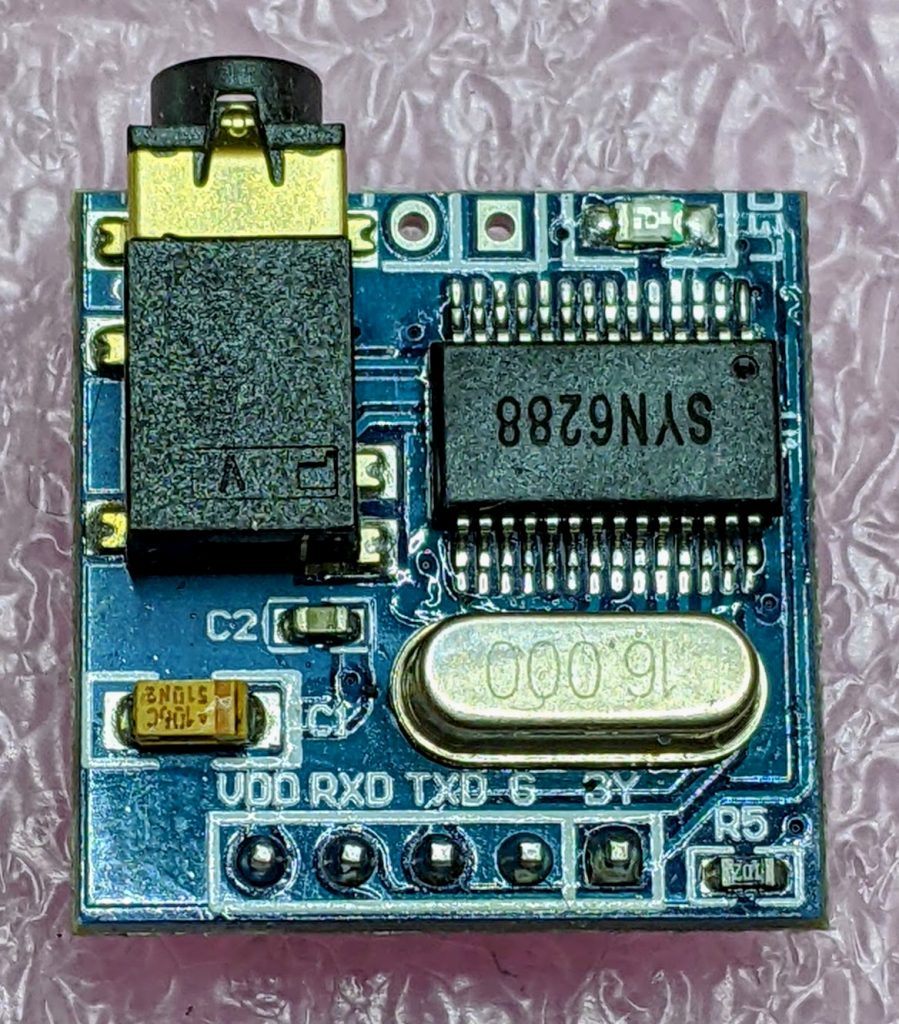

After remarkable success with the SYN-6988 TTS module, then somewhat less success with the SYN-6658 and other modules, I didn’t hold out much hope for the YuTone SYN-6288, which – while boasting a load of background tunes that could play over speech – can only convert Chinese text to speech

The wiring is similar to the SYN-6988: a serial UART connection at 9600 baud, plus a Busy (BY) line to signal when the chip is busy. The serial protocol is slightly more complicated, as the SYN-6288 requires a checksum byte at the end.

As I’m not interested in the text-to-speech output itself, here’s a MicroPython script to play all of the sounds:

# very crude MicroPython demo of SYN6288 TTS chip

# scruss, 2023-07

import machine

import time

### setup device

ser = machine.UART(

0, baudrate=9600, bits=8, parity=None, stop=1

) # tx=Pin(0), rx=Pin(1)

busyPin = machine.Pin(2, machine.Pin.IN, machine.Pin.PULL_UP)

def sendspeak(u2, data, busy):

# modified from https://github.com/TPYBoard/TPYBoard_lib/

# u2 = UART(uart, baud)

eec = 0

buf = [0xFD, 0x00, 0, 0x01, 0x01]

# buf = [0xFD, 0x00, 0, 0x01, 0x79] # plays with bg music 15

buf[2] = len(data) + 3

buf += list(bytearray(data, "utf-8"))

for i in range(len(buf)):

eec ^= int(buf[i])

buf.append(eec)

u2.write(bytearray(buf))

while busy.value() != True:

# wait for busy line to go high

time.sleep_ms(5)

while busy.value() == True:

# wait for it to finish

time.sleep_ms(5)

for s in "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxy":

playstr = "[v10][x1]sound" + s

print(playstr)

sendspeak(ser, playstr, busyPin)

time.sleep(2)

for s in "abcdefgh":

playstr = "[v10][x1]msg" + s

print(playstr)

sendspeak(ser, playstr, busyPin)

time.sleep(2)

for s in "abcdefghijklmno":

playstr = "[v10][x1]ring" + s

print(playstr)

sendspeak(ser, playstr, busyPin)

time.sleep(2)

Each sound starts and stops with a very loud click, and the sound quality is not great. I couldn’t get a good recording of the sounds (some of which of which are over a minute long) as the only way I could get reliable audio output was through tiny headphones. Any recording came out hopelessly distorted:

I’m not too disappointed that this didn’t work well. I now know that the SYN-6988 is the good one to get. It also looks like I may never get to try the XFS5152CE speech synthesizer board: AliExpress has cancelled my shipment for no reason. It’s supposed to have some English TTS function, even if quite limited.

Here’s the auto-translated SYN-6288 manual, if you do end up finding a use for the thing

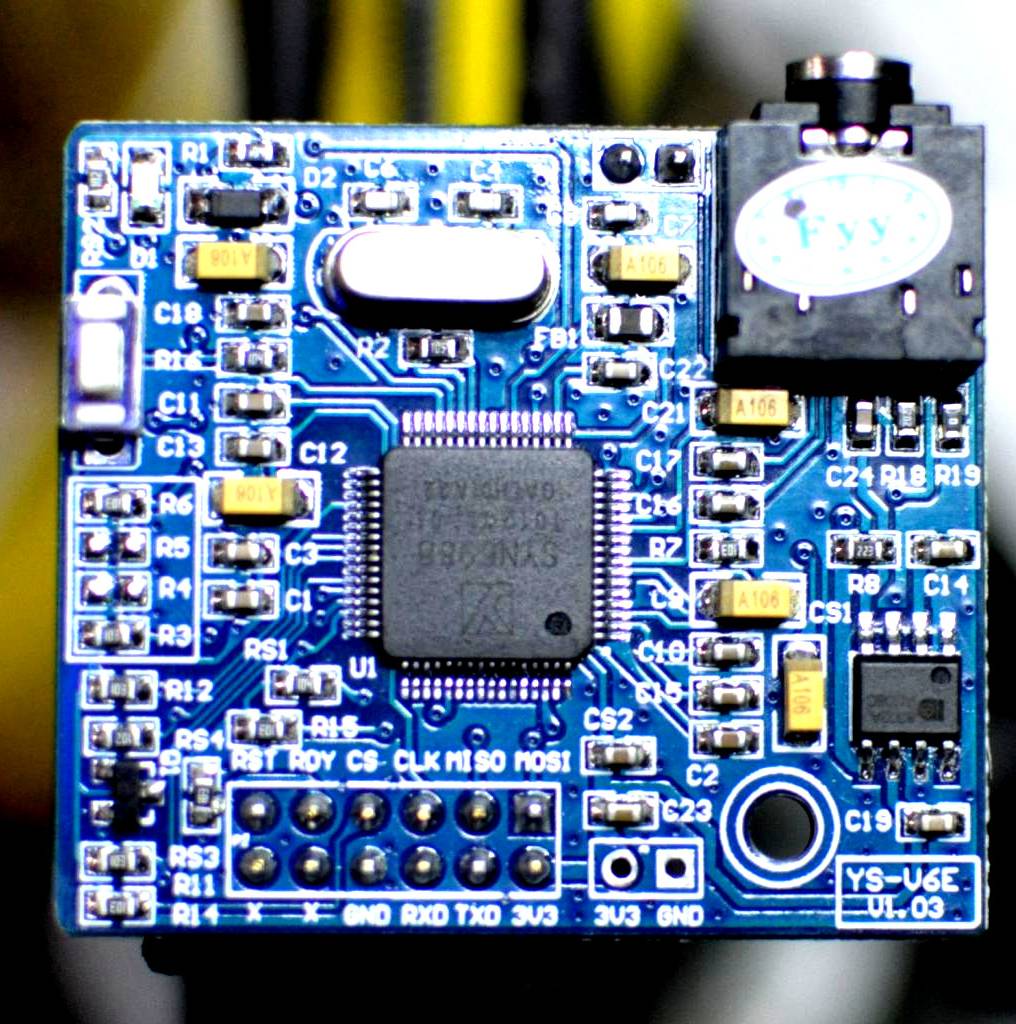

Yup, it’s another “let’s wire up a SYN6988 board” thing, this time for MMBasic running on the Armmite STM32F407 Module (aka ‘Armmite F4’). This board is also known as the BLACK_F407VE, which also makes a nice little MicroPython platform.

Uh, let’s not dwell too much on how the SYN6988 seems to parse 19:51 as “91 minutes to 20” …

| SYN6988 | Armmite F4 |

| RX | PA09 (COM1 TX) |

| TX | PA10 (COM1 RX) |

| RDY | PA08 |

Where to buy: AliExpress — KAIKAI Electronics Wholesale Store : High-end Speech Synthesis Module Chinese/English Speech Synthesis XFS5152 Real Pronunciation TTS

Yes, I know it says it’s an XFS5152, but I got a SYN6988 and it seems to be about as reliable a source as one can find. The board is marked YS-V6E-V1.03, and even mentions SYN6988 on the rear silkscreen:

REM SYN6988 speech demo - MMBasic / Armmite F4

REM scruss, 2023-07

OPEN "COM1:9600" AS #5

REM READY line on PA8

SETPIN PA8, DIN, PULLUP

REM you can ignore font/text commands

CLS

FONT 1

TEXT 0,15,"[v1]Hello - this is a speech demo."

say("[v1]Hello - this is a speech demo.")

TEXT 0,30,"[x1]soundy[d]"

say("[x1]soundy[d]"): REM chimes

TEXT 0,45,"The time is "+LEFT$(TIME$,5)+"."

say("The time is "+LEFT$(TIME$,5)+".")

END

SUB say(a$)

LOCAL dl%,maxlof%

REM data length is text length + 2 (for the 1 and 0 bytes)

dl%=2+LEN(a$)

maxlof%=LOF(#5)

REM SYN6988 simple data packet

REM byte 1 : &HFD

REM byte 2 : data length (high byte)

REM byte 3 : data length (low byte)

REM byte 4 : &H01

REM byte 5 : &H00

REM bytes 6-: ASCII string data

PRINT #5, CHR$(&hFD)+CHR$(dl%\256)+CHR$(dl% MOD 256)+CHR$(1)+CHR$(0)+a$;

DO WHILE LOF(#5)<maxlof%

REM pause while sending text

PAUSE 5

LOOP

DO WHILE PIN(PA8)<>1

REM wait until RDY is high

PAUSE 5

LOOP

DO WHILE PIN(PA8)<>0

REM wait until SYN6988 signals READY

PAUSE 5

LOOP

END SUB

For more commands, please see Embedded text commands

Heres the auto-translated manual for the SYN6988:

The other week’s success with the SYN6988 TTS chip was not repeated with three other modules I ordered, alas. Two of them I couldn’t get a peep out of, the other didn’t support English text-to-speech.

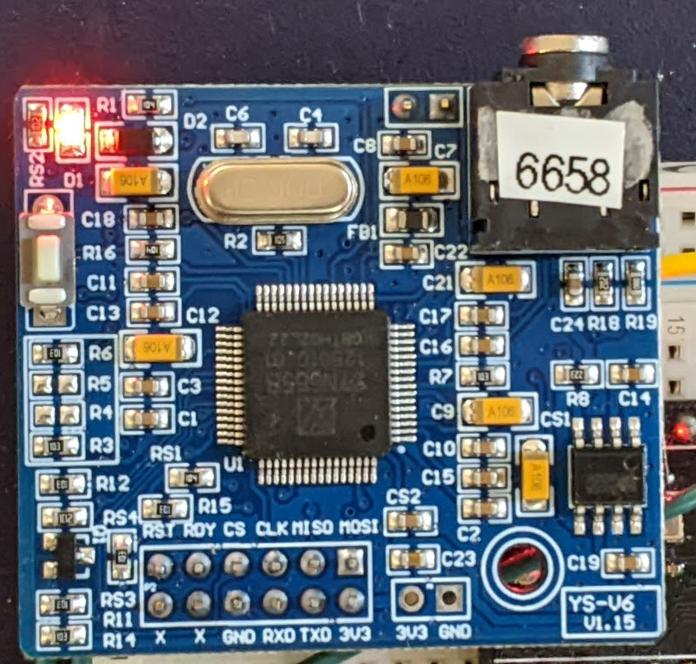

This one looks remarkably like the SYN6988:

Apart from the main chip, the only difference appears to be that the board’s silkscreen says YS-V6 V1.15 where the SYN6988’s said YS-V6E V1.02.

To be fair to YuTone (the manufacturer), they claim this only supports Chinese as an input language. If you feed it English, at best you’ll get it spelling out the letters. It does have quite a few amusing sounds, though, so at least you can make it beep and chime. My MicroPython library for the VoiceTX SYN6988 text to speech module can drive it as far as I understand it.

Here are the sounds:

| Name | Type | Link |

|---|---|---|

| msga | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgb | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgc | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgd | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msge | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgf | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgg | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgh | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgi | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgj | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgk | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgl | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgm | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| msgn | Polyphonic Chord Beep | |

| sound101 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound102 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound103 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound104 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound105 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound106 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound107 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound108 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound109 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound110 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound111 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound112 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound113 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound114 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound115 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound116 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound117 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound118 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound119 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound120 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound121 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound122 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound123 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound124 | Prompt Tone | |

| sound201 | phone ringtone | |

| sound202 | phone ringtone | |

| sound203 | phone ringtone | |

| sound204 | phone ringing | |

| sound205 | phone ringtone | |

| sound206 | door bell | |

| sound207 | door bell | |

| sound208 | doorbell | |

| sound209 | door bell | |

| sound210 | alarm | |

| sound211 | alarm | |

| sound212 | alarm | |

| sound213 | alarm | |

| sound214 | wind chimes | |

| sound215 | wind chimes | |

| sound216 | wind chimes | |

| sound217 | wind chimes | |

| sound218 | wind chimes | |

| sound219 | wind chimes | |

| sound301 | alarm | |

| sound302 | alarm | |

| sound303 | alarm | |

| sound304 | alarm | |

| sound305 | alarm | |

| sound306 | alarm | |

| sound307 | alarm | |

| sound308 | alarm | |

| sound309 | alarm | |

| sound310 | alarm | |

| sound311 | alarm | |

| sound312 | alarm | |

| sound313 | alarm | |

| sound314 | alarm | |

| sound315 | alert-emergency | |

| sound316 | alert-emergency | |

| sound317 | alert-emergency | |

| sound318 | alert-emergency | |

| sound319 | alert-emergency | |

| sound401 | credit card successful | |

| sound402 | credit card successful | |

| sound403 | credit card successful | |

| sound404 | credit card successful | |

| sound405 | credit card successful | |

| sound406 | credit card successful | |

| sound407 | credit card successful | |

| sound408 | successfully swiped the card | |

| sound501 | cuckoo | |

| sound502 | error | |

| sound503 | applause | |

| sound504 | laser | |

| sound505 | laser | |

| sound506 | landing | |

| sound507 | gunshot | |

| sound601 | alarm sound / air raid siren (long) | |

| sound602 | prelude to weather forecast (long) |

Where I bought it: Electronic Component Module Store : Chinese-to-real-life Speech Synthesis Playing Module TTS Announcer SYN6658 of Bank Bus Broadcasting.

Auto-translated manual:

All I could get from this one was a power-on chime. The main chip has had its markings ground off, so I’ve no idea what it is.

Red and black wires seem to be standard 5 V power. Yellow seems to be serial in, white is not connected.

Where I bought it: Electronic Component Module Store / Chinese TTS Text-to-speech Broadcast Synthesis Module MCU Serial Port Robot Plays Prompt Advertising Board

In theory, this little board has a lot going for it: wifi, bluetooth, commands sent by AT commands. In practice, I couldn’t get it to do a thing.

Where I bought it: HI-LINK Component Store / HLK-V40 Speech Synthesis Module TTS Pure Text to Speech Playback Hailinco AI intelligent Speech Synthesis Broadcast

I’ve still got a SYN6288 to look at, plus a XFS5152CE TTS that’s in the mail that may or may not be in the mail. The SYN6988 is the best of the bunch so far.

Full repo, with module and instructions, here: scruss/micropython-SYN6988: MicroPython library for the VoiceTX SYN6988 text to speech module

(and for those that CircuitPython is the sort of thing they like, there’s this: scruss/circuitpython-SYN6988: CircuitPython library for the YuTone VoiceTX SYN6988 text to speech module.)

I have a bunch of other boards on order to see if the other chips (SYN6288, SYN6658, XF5152) work in the same way. I really wonder which I’ll end up receiving!

Update (2023-07-09): Got the SYN6658. It does not support English TTS and thus is not recommended. It does have some cool sounds, though.

The github repo references Embedded text commands, but all of the sound references was too difficult to paste into a table there. So here are all of the ones that the SYN-6988 knows about:

| Name | Alias | Type | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| sound101 | sounda | ||

| sound102 | soundb | ||

| sound103 | soundc | ||

| sound104 | soundd | ||

| sound105 | sounde | ||

| sound106 | soundf | ||

| sound107 | soundg | ||

| sound108 | soundh | ||

| sound109 | soundi | ||

| sound110 | soundj | ||

| sound111 | soundk | ||

| sound112 | soundl | ||

| sound113 | soundm | ||

| sound114 | soundn | ||

| sound115 | soundo | ||

| sound116 | soundp | ||

| sound117 | soundq | ||

| sound118 | soundr | ||

| sound119 | soundt | ||

| sound120 | soundu | ||

| sound121 | soundv | ||

| sound122 | soundw | ||

| sound123 | soundx | ||

| sound124 | soundy | ||

| sound201 | phone ringtone | ||

| sound202 | phone ringtone | ||

| sound203 | phone ringtone | ||

| sound204 | phone rings | ||

| sound205 | phone ringtone | ||

| sound206 | doorbell | ||

| sound207 | doorbell | ||

| sound208 | doorbell | ||

| sound209 | doorbell | ||

| sound301 | alarm | ||

| sound302 | alarm | ||

| sound303 | alarm | ||

| sound304 | alarm | ||

| sound305 | alarm | ||

| sound306 | alarm | ||

| sound307 | alarm | ||

| sound308 | alarm | ||

| sound309 | alarm | ||

| sound310 | alarm | ||

| sound311 | alarm | ||

| sound312 | alarm | ||

| sound313 | alarm | ||

| sound314 | alarm | ||

| sound315 | alert/emergency | ||

| sound316 | alert/emergency | ||

| sound317 | alert/emergency | ||

| sound318 | alert/emergency | ||

| sound401 | credit card successful | ||

| sound402 | credit card successful | ||

| sound403 | credit card successful | ||

| sound404 | credit card successful | ||

| sound405 | credit card successful | ||

| sound406 | credit card successful | ||

| sound407 | credit card successful | ||

| sound408 | successfully swiped the card |

I’ve had one of these cheap(ish – $15) sound modules from AliExpress for a while. I hadn’t managed to get much out of it before, but I poked about at it a little more and found I was trying to drive the wrong chip. Aha! Makes all the difference.

So here’s a short narration from my favourite Richard Brautigan poem, read by the SYN6988.

Sensitive listener alert! There is a static click midway through. I edited out the clipped part, but it’s still a little jarring. It would always do this at the same point in playback, for some reason.

The only Pythonish code I could find for these chips was meant for the older SYN6288 and MicroPython (syn6288.py). I have no idea what I’m doing, but with some trivial modification, it makes sound.

I used the simple serial UART connection: RX -> TX, TX -> RX, 3V3 to 3V3 and GND to GND. My board is hard-coded to run at 9600 baud. I used the USB serial adapter that came with the board.

Here’s the code that read that text:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

import serial

import time

# NB via MicroPython and old too! Also for a SYN6288, which I don't have

# nabbed from https://github.com/TPYBoard/TPYBoard_lib/

def sendspeak(port, data):

eec = 0

buf = [0xFD, 0x00, 0, 0x01, 0x01]

buf[2] = len(data) + 3

buf += list(bytearray(data, encoding='utf-8'))

for i in range(len(buf)):

eec ^= int(buf[i])

buf.append(eec)

port.write(bytearray(buf))

ser = serial.Serial("/dev/ttyUSB1", 9600)

sendspeak(ser, "[t5]I like to think [p100](it [t7]has[t5] to be!)[p100] of a cybernetic ecology [p100]where we are free of our labors and joined back to nature, [p100]returned to our mammal brothers and sisters, [p100]and all watched over by machines of loving grace")

time.sleep(8)

ser.close()

This code is bad. All I did was prod stuff until it stopped not working. Since all I have to work from includes a datasheet in Chinese (from here: ??????-SYN6988???TTS????) there’s lots of stuff I could do better. I used the tone and pause tags to give the reading a little more life, but it’s still a bit flat. For $15, though, a board that makes a fair stab at reading English is not bad at all. We can’t all afford vintage DECtalk hardware.

The one thing I didn’t do is used the SYN6988’s Busy/Ready line to see if it was still busy reading. That means I could send it text as soon as it was ready, rather than pausing for 8 seconds after the speech. This refinement will come later, most likely when I port this to MicroPython.

More resources:

It’s now possible to build and run the DECtalk text to speech system on Linux. It even builds under emscripten, enabling DECtalk for Web in your browser. You too can annoy everyone within earshot making it prattle on about John Madden.

But DECTalk can sing! Because it’s been around so long, there are huge archives of songs in DECtalk format out there. The largest archive is at THE FLAME OF HOPE website, under the Dectalk section.

Building DECtalk songs isn’t easy, especially for a musical numpty like me. You need a decent grasp of music notation, phonemic/phonetic markup and patience with DECtalk’s weird and ancient text formats.

While DECtalk can accept text and turn it into a fair approximation of spoken English, for singing you have to use phonemes. Let’s say we have a solfège-ish major scale:

do re mi fa sol la ti do

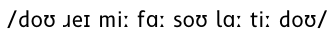

If we’re all fancy-like and know our International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), that would translate to:

/doʊ ɹeɪ miː faː soʊ laː tiː doʊ/

or if your fonts aren’t up to IPA:

DECtalk uses a variant on the ARPABET convention to represent IPA symbols as ASCII text. The initial consonant sounds remain as you might expect: D, R, M, F, S, L and T. The vowel sounds, however, are much more complex. This will give us a DECtalk-speakable phrase:

[dow rey miy faa sow laa tiy dow].

Note the opening and closing brackets and the full stop at the end. The brackets introduce phonemes, and the full stop tells DECtalk that the text is at an end. Play it in the DECtalk for Web window and be unimpressed: while the pitch changes are non-existent, the sounds are about right.

For more information about DECtalk phonemes, please see Phonemic Symbols Listed By Language and chapter 7 of DECtalk DTC03 Text-to-Speech System Owner’s Manual.

If you want to have a rough idea of what the phonemes in a phrase might be, you can use DECtalk’s :log phonemes option. You might still have to massage the input and output a bit, like using sed to remove language codes:

say -l us -pre '[:log phonemes on]' -post '[:log phonemes off]' -a "doe ray me fah so lah tea doe" | sed 's/us_//g;' d ' ow r ' ey m iy f ' aa) s ow ll' aa t ' iy d ' ow.

To me — a not very musical person — staff notation looks like it was designed by a maniac. A more impractical system to indicate arrangement of notes and their durations I don’t think I could come up with: and yet we’re stuck with it.

DECtalk uses a series of numbered pitches plus durations in milliseconds for its singing mode. The notes (1–37) correspond to C2 to C5. If you’re familiar with MIDI note numbers, DECtalk’s 1–37 correspond to MIDI note numbers 36–72. This is how DECtalk’s pitch numbers would look as major scales on the treble clef:

I’m not sure browsers can play MIDI any more, but here you go (doremi-abc.mid):

and since I had to learn abc notation to make these noises, here is the source:

%abc-2.1 X:1 T:Do Re Mi C:Trad. M:4/4 L:1/4 Q:1/4=120 K:C %1 C,, D,, E,, F,,| G,, A,, B,, C,| D, E, F, G,| A, B, C D| E F G A| B c z2 |] w:do re mi fa sol la ti do re mi fa sol la ti do re mi fa sol la ti do

Each element of a DECtalk song takes the following form:

phoneme <duration, pitch number>

The older DTC-03 manual hints that it takes around 100 ms for DECtalk to hit pitch, so for each ½ second utterance (or quarter note at 120 bpm, ish), I split it up as:

So the three lowest notes in the major scale would sing as:

[d<100,1>ow<337,1>_<63> r<100,3>ey<337,3>_<63> m<100,5>iy<337,5>_<63>].

I’ve split them into line for ease of reading, but DECtalk adds extra pauses if you include spaces, so don’t.

The full three octave major scale looks like this:

[d<100,1>ow<337,1>_<63>r<100,3>ey<337,3>_<63>m<100,5>iy<337,5>_<63>f<100,6>aa<337,6>_<63>s<100,8>ow<337,8>_<63>l<100,10>aa<337,10>_<63>t<100,12>iy<337,12>_<63>d<100,13>ow<337,13>_<63>r<100,15>ey<337,15>_<63>m<100,17>iy<337,17>_<63>f<100,18>aa<337,18>_<63>s<100,20>ow<337,20>_<63>l<100,22>aa<337,22>_<63>t<100,24>iy<337,24>_<63>d<100,25>ow<337,25>_<63>r<100,27>ey<337,27>_<63>m<100,29>iy<337,29>_<63>f<100,30>aa<337,30>_<63>s<100,32>ow<337,32>_<63>l<100,34>aa<337,34>_<63>t<100,36>iy<337,36>_<63>d<100,37>ow<337,37>_<63>].

You can paste that into the DECtalk browser window, or run the following from the command line on Linux:

say -pre '[:PHONE ON]' -a '[d<100,1>ow<337,1>_<63>r<100,3>ey<337,3>_<63>m<100,5>iy<337,5>_<63>f<100,6>aa<337,6>_<63>s<100,8>ow<337,8>_<63>l<100,10>aa<337,10>_<63>t<100,12>iy<337,12>_<63>d<100,13>ow<337,13>_<63>r<100,15>ey<337,15>_<63>m<100,17>iy<337,17>_<63>f<100,18>aa<337,18>_<63>s<100,20>ow<337,20>_<63>l<100,22>aa<337,22>_<63>t<100,24>iy<337,24>_<63>d<100,25>ow<337,25>_<63>r<100,27>ey<337,27>_<63>m<100,29>iy<337,29>_<63>f<100,30>aa<337,30>_<63>s<100,32>ow<337,32>_<63>l<100,34>aa<337,34>_<63>t<100,36>iy<337,36>_<63>d<100,37>ow<337,37>_<63>].'

It sounds like this:

Singing a scale is hardly singing a tune, but hey, you were warned that this was a terrible guide at the outset. I hope I’ve given you a start on which you can build your own songs.

(One detail I haven’t tried yet: the older DTC-03 manual hints that singing notes can take Hz values instead of pitch numbers, and apparently loses the vibrato effect. It’s not that hard to convert from a note/octave to a frequency. Whether this still works, I don’t know.)

This post from Patrick Perdue suggested to me I had to dig into the Hz value substitution because the results are so gloriously awful. Of course, I had to write a Perl regex to make the conversions from DECtalk 1–37 sung notes to frequencies from 65–523 Hz:

perl -pwle 's|(?<=,)(\d+)(?=>)|sprintf("%.0f", 440*2**(($1-34)/12))|eg;'

(as one does). So the sung scale ends up as this non-vibrato text:

say -pre '[:PHONE ON]' -a '[d<100,65>ow<337,65>_<63>r<100,73>ey<337,73>_<63>m<100,82>iy<337,82>_<63>f<100,87>aa<337,87>_<63>s<100,98>ow<337,98>_<63>l<100,110>aa<337,110>_<63>t<100,123>iy<337,123>_<63>d<100,131>ow<337,131>_<63>r<100,147>ey<337,147>_<63>m<100,165>iy<337,165>_<63>f<100,175>aa<337,175>_<63>s<100,196>ow<337,196>_<63>l<100,220>aa<337,220>_<63>t<100,247>iy<337,247>_<63>d<100,262>ow<337,262>_<63>r<100,294>ey<337,294>_<63>m<100,330>iy<337,330>_<63>f<100,349>aa<337,349>_<63>s<100,392>ow<337,392>_<63>l<100,440>aa<337,440>_<63>t<100,494>iy<337,494>_<63>d<100,523>ow<337,523>_<63>].'

That doesn’t sound as wondrously terrible as it should, most probably as they are very small differences between each sung word. So how about we try something better? Like the refrain from The Turtles’ Happy Together, as posted on TheFlameOfHope:

say -pre '[:PHONE ON]' -a '[:nv] [:dv gn 73] [AY<400,29> KAE<200,24> N<100> T<100> SIY<400,21> MIY<400,17> LAH<200,15> VAH<125,19> N<75> NOW<400,22> BAH<200,26> DXIY<200,27> BAH<300,26> T<100> YU<600,24> FOR<200,21> AO<300,24> LX<100> MAY<400,26> LAY<900,27> F<300> _<400> WEH<300,29> N<100> YXOR<400,24> NIR<400,21> MIY<400,17> BEY<200,15> BIY<200,19> DHAX<400,22> SKAY<125,26> Z<75> WIH<125,27> LX<75> BIY<400,26> BLUW<600,24> FOR<200,21> AO<300,24> LX<100> MAY<400,26> LAY<900,27> F<300> _<300> ].'

“Refrain” is a good word, as it’s exactly what I should have done, rather than commit a terribleness on the audio by de-vibratoing it:

say -pre '[:PHONE ON]' -a '[:nv] [:dv gn 73] [AY<400,330> KAE<200,247> N<100> T<100> SIY<400,208> MIY<400,165> LAH<200,147> VAH<125,185> N<75> NOW<400,220> BAH<200,277> DXIY<200,294> BAH<300,277> T<100> YU<600,247> FOR<200,208> AO<300,247> LX<100> MAY<400,277> LAY<900,294> F<300> _<400> WEH<300,330> N<100> YXOR<400,247> NIR<400,208> MIY<400,165> BEY<200,147> BIY<200,185> DHAX<400,220> SKAY<125,277> Z<75> WIH<125,294> LX<75> BIY<400,277> BLUW<600,247> FOR<200,208> AO<300,247> LX<100> MAY<400,277> LAY<900,294> F<300> _<300> ].'

Oh dear. You can’t unhear that, can you?

I can’t believe I’m having to write this article again. Back in 2004, I picked up an identical model of typewriter on Freecycle, also complete with the parallel printer option board. The one I had back then had an incredible selection of printwheels. And I gave it all away! Aaargh! Why?

Last month, I ventured out to a Value Village in more affluent part of town. On the shelf for $21 was a familiar boxy shape, another Wheelwriter 10 Series II Typewriter model 6783. This one also has the printer option board, but it only has one printwheel, Prestige Elite. It powered on enough at the test rack enough for me to see it mostly worked, so I bought it.

Once I got it home, though, I could see it needed some work. The platen was covered in ink and correction fluid splatters. Worse, the carriage would jam in random places. It was full of dust and paperclips. But the printwheel did make crisp marks on paper, so it was worth looking at a repair.

Thanks to Phoenix Typewriter’s repair video “IBM Wheelwriter Typewriter Repair Fix Carriage Carrier Sticks Margins Reset Makes Noise”, I got it going again. I’m not sure how much life I’ve got left in the film ribbon, but for now it’s doing great.

Note that there are lots of electronics projects — such as tofergregg/IBM-Wheelwriter-Hack: Turning an IBM Wheelwriter into a unique printer — that use an Arduino or similar to drive the printer. This is not that (or those). Here I’m using the Printer Option board plus a USB to Parallel cable. There’s almost nothing out there about how these work.

You’ll need a USB to Parallel adapter, something like this: StarTech 10 ft USB to Parallel Printer Adapter – M/M. You need the kind with the big Centronics connector, not the 25-pin D-type. My one (old) has a chunky plastic case that won’t fit into the port on the Wheelwriter unless you remove part of the cable housing. On my Linux box, the port device is /dev/usb/lp0. You might want to add yourself to the lp group so you can send data to the printer without using sudo:

sudo adduser user lpThe Wheelwriter needs to be switched into printer mode manually by pressing the Code + Printer Enable keys.

As far as I can tell, the Wheelwriter understands a subset of IBM ProPrinter codes. Like most simple printers, most control codes start with an Esc character (ASCII 27). Lines need to end with both a Carriage Return (ASCII 13) and newline (ASCII 10). Sending only CRs allows overprinting, while sending only newlines gives stair-step output.

The codes I’ve found to work so far are:

Text functions such as italics and extended text aren’t possible with a daisywheel printer. You can attempt dot-matrix graphics using full stops and micro spacing, but I don’t want to know you if you’d try.

echo is about the simplest way of doing it. Some systems provide an echo built-in that doesn’t support the -e (interpret special characters) and -n (don’t send newline) options. You may have to call /usr/bin/echo instead.

To print emphasized:

echo -en 'well \eEhello\eF there!\r\n' > /dev/usb/lp0which prints

well hello there!To print underlined:

echo -en 'well \e-1hello\e-0 there!\r\n' > /dev/usb/lp0which types

well hello there!To set the line spacing to a (very cramped) 1/12″ [= 2.1 mm] and print a horizontal line of dots and a vertical line of dots, both equally spaced (if you’re using Prestige Elite):

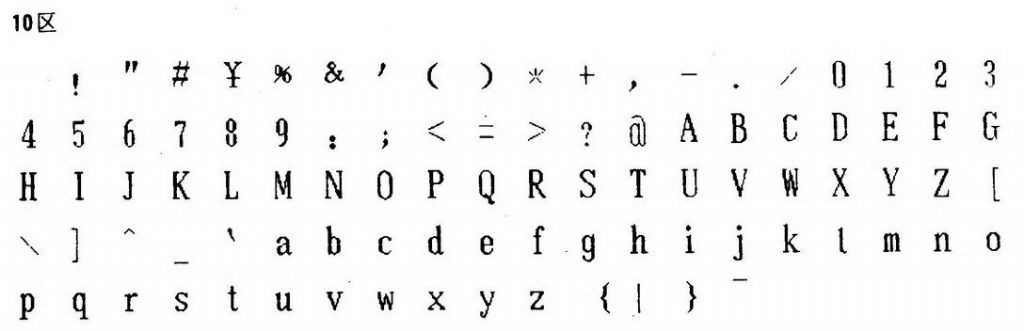

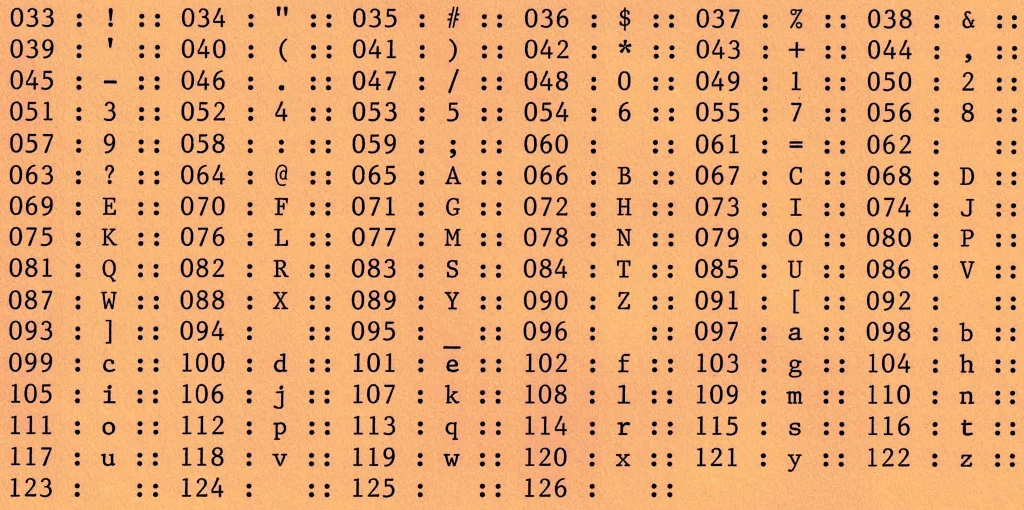

echo -en '\eA\x05\e2\r\n..........\r\n.\r\n.\r\n.\r\n.\r\n.\r\n.\r\n.\r\n.\r\n.\r\n\r\n' > /dev/usb/lp0IBM daisywheels typically can’t represent the whole ASCII character set. Here’s what an attempt to print codes 33 to 126 in Prestige Elite looks like:

The following characters are missing:

< > \ ^ ` { | } ~So printing your HTML or Python is right out. FORTRAN, as ever, is safe.

Prestige Elite is a 12 character per inch font (“12 pitch”, or even “Elite” in typewriter parlance) that’s mostly been overshadowed by Courier (typically 10 characters per inch) in computer usage. This is a shame, as it’s a much prettier font.

There’s very little out there about printing with IBM daisywheels. This is a dump of the stuff I’ve found that may help other people: