It’s now possible to build and run the DECtalk text to speech system on Linux. It even builds under emscripten, enabling DECtalk for Web in your browser. You too can annoy everyone within earshot making it prattle on about John Madden.

But DECTalk can sing! Because it’s been around so long, there are huge archives of songs in DECtalk format out there. The largest archive is at THE FLAME OF HOPE website, under the Dectalk section.

Building DECtalk songs isn’t easy, especially for a musical numpty like me. You need a decent grasp of music notation, phonemic/phonetic markup and patience with DECtalk’s weird and ancient text formats.

DECtalk phonemes

While DECtalk can accept text and turn it into a fair approximation of spoken English, for singing you have to use phonemes. Let’s say we have a solfège-ish major scale:

do re mi fa sol la ti do

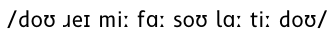

If we’re all fancy-like and know our International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), that would translate to:

/doʊ ɹeɪ miː faː soʊ laː tiː doʊ/

or if your fonts aren’t up to IPA:

DECtalk uses a variant on the ARPABET convention to represent IPA symbols as ASCII text. The initial consonant sounds remain as you might expect: D, R, M, F, S, L and T. The vowel sounds, however, are much more complex. This will give us a DECtalk-speakable phrase:

[dow rey miy faa sow laa tiy dow].

Note the opening and closing brackets and the full stop at the end. The brackets introduce phonemes, and the full stop tells DECtalk that the text is at an end. Play it in the DECtalk for Web window and be unimpressed: while the pitch changes are non-existent, the sounds are about right.

For more information about DECtalk phonemes, please see Phonemic Symbols Listed By Language and chapter 7 of DECtalk DTC03 Text-to-Speech System Owner’s Manual.

If you want to have a rough idea of what the phonemes in a phrase might be, you can use DECtalk’s :log phonemes option. You might still have to massage the input and output a bit, like using sed to remove language codes:

say -l us -pre '[:log phonemes on]' -post '[:log phonemes off]' -a "doe ray me fah so lah tea doe" | sed 's/us_//g;' d ' ow r ' ey m iy f ' aa) s ow ll' aa t ' iy d ' ow.

Music notation

To me — a not very musical person — staff notation looks like it was designed by a maniac. A more impractical system to indicate arrangement of notes and their durations I don’t think I could come up with: and yet we’re stuck with it.

DECtalk uses a series of numbered pitches plus durations in milliseconds for its singing mode. The notes (1–37) correspond to C2 to C5. If you’re familiar with MIDI note numbers, DECtalk’s 1–37 correspond to MIDI note numbers 36–72. This is how DECtalk’s pitch numbers would look as major scales on the treble clef:

I’m not sure browsers can play MIDI any more, but here you go (doremi-abc.mid):

and since I had to learn abc notation to make these noises, here is the source:

%abc-2.1 X:1 T:Do Re Mi C:Trad. M:4/4 L:1/4 Q:1/4=120 K:C %1 C,, D,, E,, F,,| G,, A,, B,, C,| D, E, F, G,| A, B, C D| E F G A| B c z2 |] w:do re mi fa sol la ti do re mi fa sol la ti do re mi fa sol la ti do

Each element of a DECtalk song takes the following form:

phoneme <duration, pitch number>

The older DTC-03 manual hints that it takes around 100 ms for DECtalk to hit pitch, so for each ½ second utterance (or quarter note at 120 bpm, ish), I split it up as:

- 100 ms of the initial consonant;

- 337 ms of the vowel sound;

- 63 ms of pause (which has the phoneme code “_”). Pauses don’t need pitch numbers, unless you want them to preempt DECtalk’s pitch-change algorithm.

So the three lowest notes in the major scale would sing as:

[d<100,1>ow<337,1>_<63> r<100,3>ey<337,3>_<63> m<100,5>iy<337,5>_<63>].

I’ve split them into line for ease of reading, but DECtalk adds extra pauses if you include spaces, so don’t.

The full three octave major scale looks like this:

[d<100,1>ow<337,1>_<63>r<100,3>ey<337,3>_<63>m<100,5>iy<337,5>_<63>f<100,6>aa<337,6>_<63>s<100,8>ow<337,8>_<63>l<100,10>aa<337,10>_<63>t<100,12>iy<337,12>_<63>d<100,13>ow<337,13>_<63>r<100,15>ey<337,15>_<63>m<100,17>iy<337,17>_<63>f<100,18>aa<337,18>_<63>s<100,20>ow<337,20>_<63>l<100,22>aa<337,22>_<63>t<100,24>iy<337,24>_<63>d<100,25>ow<337,25>_<63>r<100,27>ey<337,27>_<63>m<100,29>iy<337,29>_<63>f<100,30>aa<337,30>_<63>s<100,32>ow<337,32>_<63>l<100,34>aa<337,34>_<63>t<100,36>iy<337,36>_<63>d<100,37>ow<337,37>_<63>].

You can paste that into the DECtalk browser window, or run the following from the command line on Linux:

say -pre '[:PHONE ON]' -a '[d<100,1>ow<337,1>_<63>r<100,3>ey<337,3>_<63>m<100,5>iy<337,5>_<63>f<100,6>aa<337,6>_<63>s<100,8>ow<337,8>_<63>l<100,10>aa<337,10>_<63>t<100,12>iy<337,12>_<63>d<100,13>ow<337,13>_<63>r<100,15>ey<337,15>_<63>m<100,17>iy<337,17>_<63>f<100,18>aa<337,18>_<63>s<100,20>ow<337,20>_<63>l<100,22>aa<337,22>_<63>t<100,24>iy<337,24>_<63>d<100,25>ow<337,25>_<63>r<100,27>ey<337,27>_<63>m<100,29>iy<337,29>_<63>f<100,30>aa<337,30>_<63>s<100,32>ow<337,32>_<63>l<100,34>aa<337,34>_<63>t<100,36>iy<337,36>_<63>d<100,37>ow<337,37>_<63>].'

It sounds like this:

Singing a scale is hardly singing a tune, but hey, you were warned that this was a terrible guide at the outset. I hope I’ve given you a start on which you can build your own songs.

(One detail I haven’t tried yet: the older DTC-03 manual hints that singing notes can take Hz values instead of pitch numbers, and apparently loses the vibrato effect. It’s not that hard to convert from a note/octave to a frequency. Whether this still works, I don’t know.)

This post from Patrick Perdue suggested to me I had to dig into the Hz value substitution because the results are so gloriously awful. Of course, I had to write a Perl regex to make the conversions from DECtalk 1–37 sung notes to frequencies from 65–523 Hz:

perl -pwle 's|(?<=,)(\d+)(?=>)|sprintf("%.0f", 440*2**(($1-34)/12))|eg;'

(as one does). So the sung scale ends up as this non-vibrato text:

say -pre '[:PHONE ON]' -a '[d<100,65>ow<337,65>_<63>r<100,73>ey<337,73>_<63>m<100,82>iy<337,82>_<63>f<100,87>aa<337,87>_<63>s<100,98>ow<337,98>_<63>l<100,110>aa<337,110>_<63>t<100,123>iy<337,123>_<63>d<100,131>ow<337,131>_<63>r<100,147>ey<337,147>_<63>m<100,165>iy<337,165>_<63>f<100,175>aa<337,175>_<63>s<100,196>ow<337,196>_<63>l<100,220>aa<337,220>_<63>t<100,247>iy<337,247>_<63>d<100,262>ow<337,262>_<63>r<100,294>ey<337,294>_<63>m<100,330>iy<337,330>_<63>f<100,349>aa<337,349>_<63>s<100,392>ow<337,392>_<63>l<100,440>aa<337,440>_<63>t<100,494>iy<337,494>_<63>d<100,523>ow<337,523>_<63>].'

That doesn’t sound as wondrously terrible as it should, most probably as they are very small differences between each sung word. So how about we try something better? Like the refrain from The Turtles’ Happy Together, as posted on TheFlameOfHope:

say -pre '[:PHONE ON]' -a '[:nv] [:dv gn 73] [AY<400,29> KAE<200,24> N<100> T<100> SIY<400,21> MIY<400,17> LAH<200,15> VAH<125,19> N<75> NOW<400,22> BAH<200,26> DXIY<200,27> BAH<300,26> T<100> YU<600,24> FOR<200,21> AO<300,24> LX<100> MAY<400,26> LAY<900,27> F<300> _<400> WEH<300,29> N<100> YXOR<400,24> NIR<400,21> MIY<400,17> BEY<200,15> BIY<200,19> DHAX<400,22> SKAY<125,26> Z<75> WIH<125,27> LX<75> BIY<400,26> BLUW<600,24> FOR<200,21> AO<300,24> LX<100> MAY<400,26> LAY<900,27> F<300> _<300> ].'

“Refrain” is a good word, as it’s exactly what I should have done, rather than commit a terribleness on the audio by de-vibratoing it:

say -pre '[:PHONE ON]' -a '[:nv] [:dv gn 73] [AY<400,330> KAE<200,247> N<100> T<100> SIY<400,208> MIY<400,165> LAH<200,147> VAH<125,185> N<75> NOW<400,220> BAH<200,277> DXIY<200,294> BAH<300,277> T<100> YU<600,247> FOR<200,208> AO<300,247> LX<100> MAY<400,277> LAY<900,294> F<300> _<400> WEH<300,330> N<100> YXOR<400,247> NIR<400,208> MIY<400,165> BEY<200,147> BIY<200,185> DHAX<400,220> SKAY<125,277> Z<75> WIH<125,294> LX<75> BIY<400,277> BLUW<600,247> FOR<200,208> AO<300,247> LX<100> MAY<400,277> LAY<900,294> F<300> _<300> ].'

Oh dear. You can’t unhear that, can you?

![[tÉ’k bÉ’ks]: case](http://scruss.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/25220880945_e5dea2e10b_z-320x241.jpg)

![[tÉ’k bÉ’ks]: inside](http://scruss.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/25193633666_517b25105c_z.jpg)