Category: goatee-stroking musing, or something

-

Gurney-7B

A minimally-useful tracing of the standard numerals embossed

on credit cards. The geometry should be checked against ISO/IEC 7811—1:2002 should these data be used for official purposes. No claims of compliance are made here.As there are only 10 digits in this font, encoding it as a digital

form (TTF, OTF, or otherwise) is left as an exercise for the reader.Files

- f7b-colour.svg – an A4 sheet with all 10 digits presented as a

poster. Each digit is approximately 1284% standard size. - eps folder – PostScript source files. Each outline is approximately 5695% standard size, which is appropriate for a glyph in FontForge.

Workflow

The rough character outlines were created as short scripts in Python,

using the Shapely library to handle geometry. A confusing array of support tools (including, but not limited to: QCAD, wellknown

and OGR added the arcs and fillets. The more complex arc intersections were calculated using GeoGebra. Finally, the

outlines — at this point, mostly in the form of PostScript Level 2

arct commands — were hand-keyed into the EPS files included here.Notes on the data

- There are some typos in the published coordinates, particularly in

the “1” glyph. Whether these are genuine errors or

‘trap streets‘, is hard to tell. The glyphs presented here are intended to be visually accurate - The published coordinates of the “8” glyph indicate that it is

only 97.6% as tall as the other digits. This has been carried

through here.

Also on github: scruss/Gurney-7B

- f7b-colour.svg – an A4 sheet with all 10 digits presented as a

-

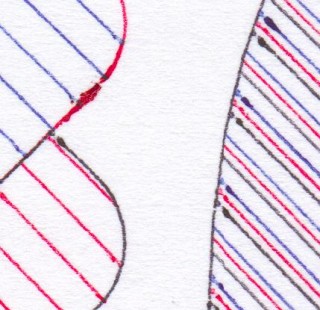

when fillets go bad

accidentally mis-sizing fillets on a character lead to this …

-

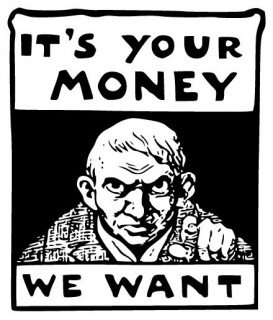

Harper, Puppeteer o’ the North

It’s the thought on everyone’s mind [photo from ‘Significant number’ of Canadian Ranger deaths flagged by military chaplain, (Chris Wattie/Reuters)]

-

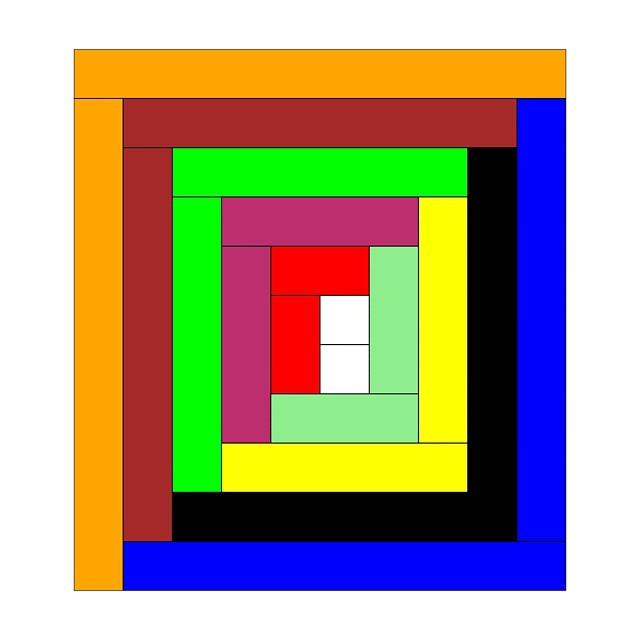

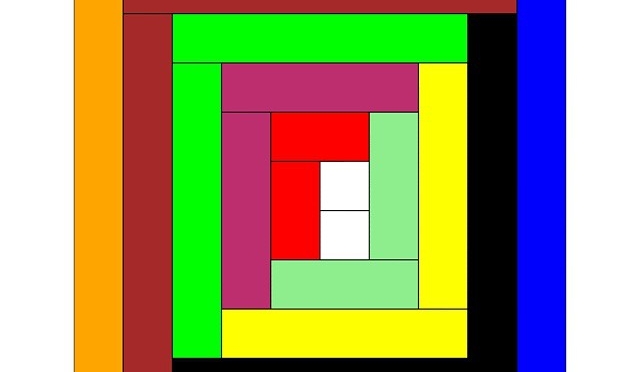

The Cuisenaire-Gattegno Log Cabin

Rods! Or more specifically, Cuisenaire® Rods! Staples of my childhood arithmetic education: coloured wooden rods (now plastic, which will save them from the mouldy fate that befell some sets at Mearns Primary School), 1 × 1 × 1–10 centimetres long. Use them for counting, number lines, don’t-do-that renditions of Sun Arise, but absolutely never for flinging at tiny classmates.

Since it may actually have been Mrs. Cuisenaire who came up with the concept of rods, I drew a log cabin quilt section in virtual rods. The Gattegno in the title refers to Caleb Gattegno, the mid-century educator who popularized Cuisenaire’s work.

Should you too feel the need to have a virtual set of rods, here are some files you can play with in Inkscape (or any other SVG-aware editor):

rods.svg — A palette of horizontal and vertical rods rods-quilt.svg – source for the header image The colours might be a bit off reality, but they’re near enough. I found it helpful to set a grid snap in Inkscape to 1 cm so that you could get the rods to align easily. If you want to get really nerdy, here’s the PostScript source I used to create the rods: rods.ps. I think I finally got the hang of basic arrays in PostScript …

Creating this was in no way a means of me displacing getting round to doing my taxes this year, nosirree.

Instagram filter used: Normal

-

The Gadsden Flag Nouveau

Instagram filter used: Normal

I made this after being inspired by this MetaFilter comment. There’s a PDF linked from the image below:

-

What a bunch of stupid Fiskars …

On the left, a very worn blade from a roughly decade-old Fiskars paper trimmer. On the right, one of the replacement blades you can get at Staples. Note the extra lugs stopping the new-style blades working with the old-style cutters? Bet they think they’re really clever little Fiskars for coming up with that planned obsolescence move.

It’s nothing that a steady hand and a rotary tool can’t fix, though …

-

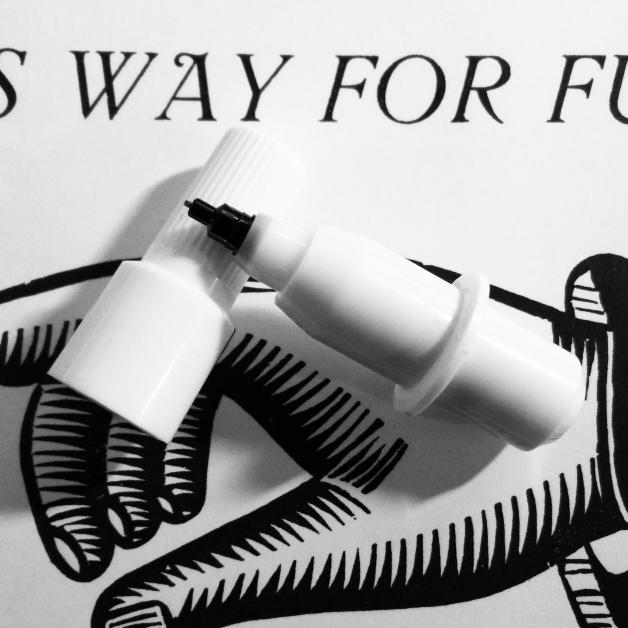

Home-brew Jetstream Plotter Pens

After a relative lack of success in making cheap plotter pens, I managed to score a trove of old pens on eBay. Some of these were dry, and I tried to resuscitate them. A few came back to life, but I ended up with a handful of very dead pen shells.

A dry plotter pen, possibly Alvin I think the pens were made or sold by Alvin, as there were several empty Alvin trays in the batch I got on eBay. In taking one apart, I thought that a pen refill might just slide inside. Lo and behold, but didn’t the pen nerd’s fave gel pen du jour refill just slide in with enough of an interference fit that it wouldn’t easily slide back out.

Taking the dry pens apart isn’t too easy:

- Pull the black tip straight out with pliers; it has a long fibre plug which goes into the ink reservoir. Discard the tip.

- While it’s really hard to see, the other end of the pen body has a push-on plug. Gently working around it with a sharp knife can open it up a bit.

- Once you’re inside the pen, pull the dry fibre ink reservoir out with tweezers and discard it.

Converting the pen body to use a Jetstream refill needs some tools:

- Drill a hole in the plug at the end of the pen body just large enough to allow the end of the refill to pass through. It helps if this is mostly centred to keep the pen point centred; this is important for accurate plots.

- Cut a piece of tubing just wide enough to slip over the pen refill, but not quite narrow enough to fit through the hole you just drilled. I used some unshrunk heatshrink tubing for this. It needs to be just long enough to push against the plug when the pen tip is at the right length. This should help stop the refill getting hammered back into the body by your plotter.

- Before you assemble the pen, I find it useful to cut a couple of flats in the sides of the plug so you can more easily change the refill. You don’t have to do this, though.

- Assemble the pen:

- Push the Jetstream refill into the pen body, and adjust it so it sticks out about 6 mm clear of the plastic collar near the nib.

- Put the tubing over the other end of the refill, and push the plug over the top, clicking it into place.

Three pens in place on my DXY-1300 To get best results, you’ll have to slow your plot speed down quite a bit. At standard speeds, you get a ¼ mm interrupted line which looks like this:

Jetstream at full speed Close up, the lines are really faint

A hint that I should run them slower was at the start of each line, where the line would start very thick, then taper off as the ink supply ran low:

A hint that I should run them slower was at the start of each line, where the line would start very thick, then taper off as the ink supply ran low:

acceleration blobs Run at 120 mm/s, the results where a bit darker, but still blobby at the start of lines:

120 mm/s Slowing down to 60 mm/s produced slightly better results:

60 mm/s But sharpest of all was at the crawling speed 30 mm/s:

30 mm/s Some pronounced blobs at the starts of lines still. Here’s the full page at 600 dpi, squished into a very lossy PDF: jetstream_plotter-slow

The blobs could be due to this, though:

grode on pen tip It seems that a mix of paper fibres and coagulated ink builds up on the tip. Occasional cleaning seems to be a good idea. It also seems to help to draw a quick scratch line before anything important so the ink will be flowing properly.

Just to sign off, here’s one of the pens in action:

-

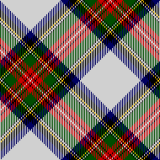

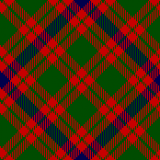

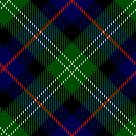

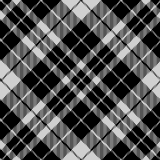

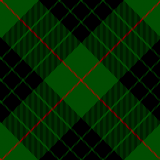

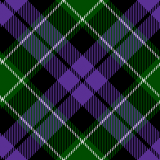

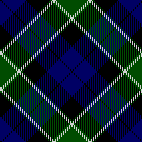

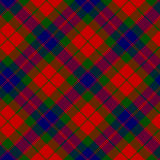

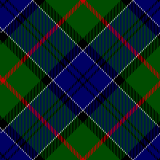

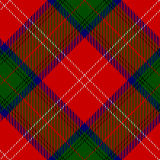

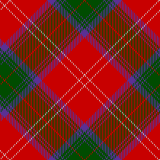

all of the tartans

I saved an archive of Robert Bradford’s mktartan program on github: scruss/holestone-tartan (local cache: holestone-tartan-master) to stop it falling apart completely from bitrot.

-

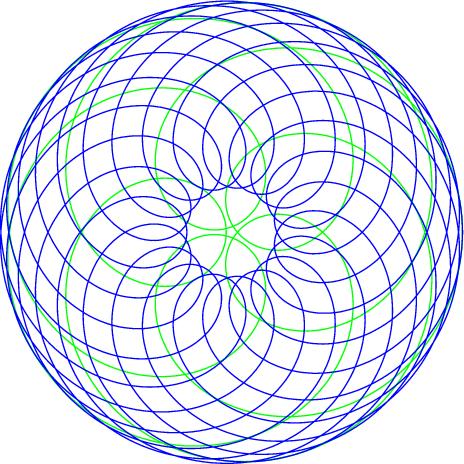

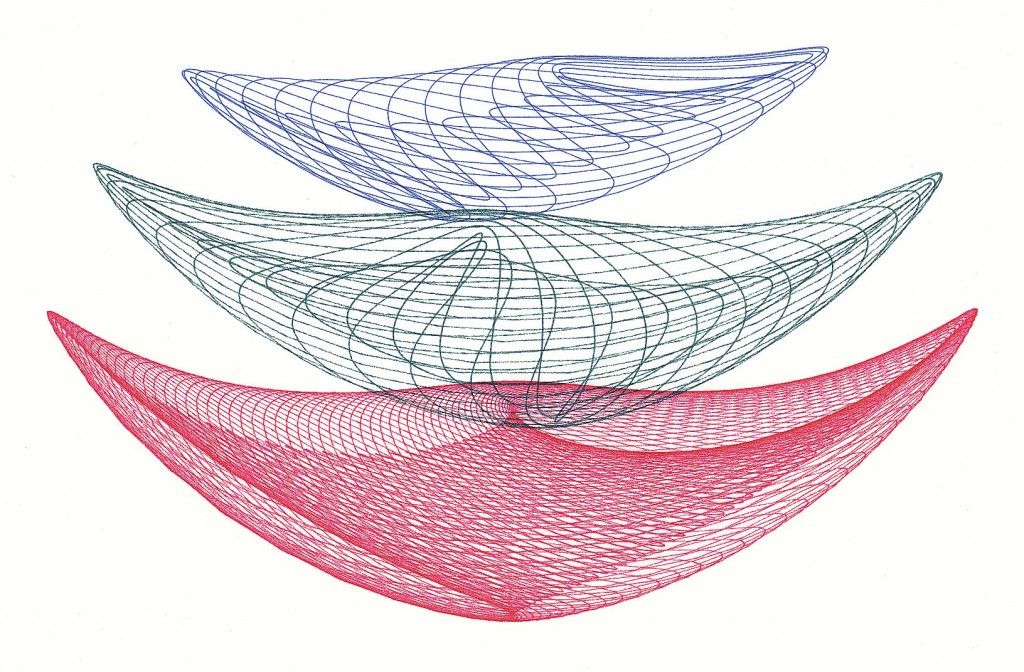

Gramophone Echoes

Inspired by Robert Howsare’s Drawing Apparatus, a time-step simulation of a similar apparatus was developed. Each trace was made of thousands of straight line segments, one for each rotation of the turntables’ drive motors, and enough to create a closed figure. Suitable gearing was modelled to simulate standard (North American) gramophone speeds of 16â…”, 33â…“, 45 and 78â…• rpm for each of the turntables. Drive crank lengths were derived from standard record sizes. The initial starting angle of each turntable was also modelled.

Inspired by Robert Howsare’s Drawing Apparatus, a time-step simulation of a similar apparatus was developed. Each trace was made of thousands of straight line segments, one for each rotation of the turntables’ drive motors, and enough to create a closed figure. Suitable gearing was modelled to simulate standard (North American) gramophone speeds of 16â…”, 33â…“, 45 and 78â…• rpm for each of the turntables. Drive crank lengths were derived from standard record sizes. The initial starting angle of each turntable was also modelled.Three simulation runs were chosen and superimposed. The result was plotted on “A†size vellum using 0.3 mm ceramic drafting pens. Total plot time at 90 mm/s: 22 minutes.

Code available on request.

-

Power, at what price?

It’s the Canadian Electricity Association’s Electricity in Ontario week. Can’t you feel it in the air? A brochure, snappily titled “ELECTRICITY ARE WE GETTING VALUE FOR THE MONEY WE PAY?†[pdf] was in my dead tree media stack this morning. I think it’s trying to say our power is too cheap, as in this graph yoinked from the text:

But as ever, hand-picked statistics only tell half the story. Digging into the IEA Key World Energy Statistics handbooks for 2011 and 2012, the data look something more like this:

Country

2010 Domestic Electricity Price / USD/kWh

2010 Annual Electricity Consumption per capita / kWh

Annual Cost per capita

Denmark

$0.356

6,329

$2,255

Japan

$0.232

8,399

$1,950

United Kingdom

$0.199

5,741

$1,142

France

$0.157

7,756

$1,216

United States

$0.116

13,361

$1,547

Canada

$0.095

15,145

$1,431

Mexico

$0.089

2,085

$185

So really, because Canadians use such an obscene amount of energy per capita (srsly; we should be ashamed of ourselves), the graph should look more like this:

So we’re not actually that inexpensive; solidly mid-range. Since our electricity price per kWh is so low, if we spent a little money on energy conservation, we could have really cheap power for everyone.

-

Screamingly fast HWRNG on Arduino Due

Well, look at this:

$ stty -F /dev/ttyACM0 speed 115200 raw cs8 $ rngtest -t 6 < /dev/ttyACM0 … much snippage … rngtest: bits received from input: 312368864 rngtest: FIPS 140-2 successes: 15602 rngtest: FIPS 140-2 failures: 16 rngtest: FIPS 140-2(2001-10-10) Monobit: 2 rngtest: FIPS 140-2(2001-10-10) Poker: 2 rngtest: FIPS 140-2(2001-10-10) Runs: 8 rngtest: FIPS 140-2(2001-10-10) Long run: 4 rngtest: FIPS 140-2(2001-10-10) Continuous run: 0 rngtest: input channel speed: (min=837.317; avg=1168.033; max=1948.060)Kibits/s rngtest: FIPS tests speed: (min=16.834; avg=27.779; max=77.221)Mibits/s rngtest: Program run time: 271917796 microseconds

Over a megabit/second of decent quality random data. This is from an Arduino Due, which has an Atmel SAM3X8E ARM Cortex-M3 microcontroller on board. I hadn’t found much use for this board previously, as it fell between a regular 8-bit Arduino and my (many!) Raspberry Pis.

This changed when I found out about Walter Anderson’s Entropy library, which uses µc timer jitter as a source of entropy. Originally designed as a slow but true source of random integers on the Atmel AVR chips, it’s been extended to use the SAM3X8E‘s built-in hardware RNG. Since the Due has a native USB port, you’re not limited to standard baud rates.

Here’s the code, trivially modified from one of Walter’s examples:

// Generate_Random_Bytes_Due - speedy demo of Arduino Due's HWRNG // based on Generate_Random_Bytes, for Entropy, an Arduino library. // Copyright 2012 by Walter Anderson // modified - scruss - 2014-08-13 // remember to reconnect to native USB port #include <Entropy.h> void setup() {  SerialUSB.begin(115200);  while (!SerialUSB) {    ; // wait for serial port to connect.  }  Entropy.initialize(); } void loop() {  uint16_t r = Entropy.random();  SerialUSB.write(lowByte(r));  SerialUSB.write(highByte(r)); }It’s a minor pain to have to reconnect the USB cable to the other port on the Arduino Due after programming, but it’s worth it just to see an 84 MHz µc belting out random bytes 37½% faster than an 800 MHz Raspberry Pi …

-

o wat

(source: https://gfycat.com/PinkEmptyGyrfalcon)

-

Solar Marble Machine at 2× speed

Solar Marble Machine – click for video For more details, please see The Solarbotics Solar Marble Machine.

Music: “A New Way of Seeing” — (excerpt) – Richard Harvey; © 1979, ICL.