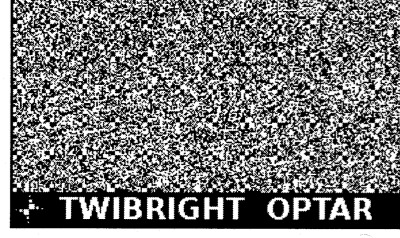

I’ve spent most of the day messing around with Twibright Optar, a way of creating printed archives of binary data that can be scanned back in and restored. It looks like it was written as a proof-of-concept, as the only way to change options is to modify the code and recompile. Eppur si muove.

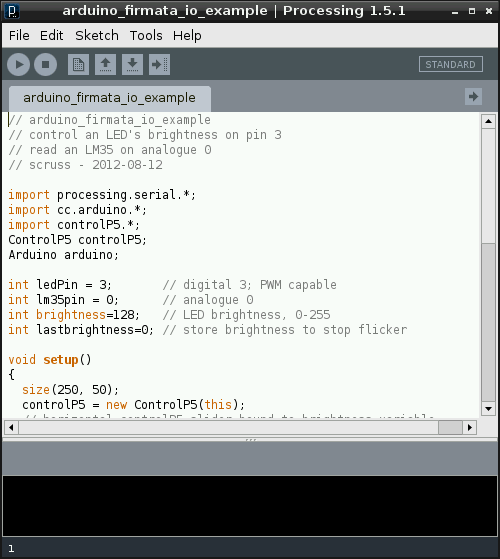

To compile the code on OS X, I found I had to change this line in the Makefile from:

LDFLAGS=-lm

to

LDFLAGS=-lm `libpng-config --L_opts`

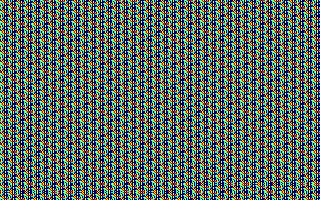

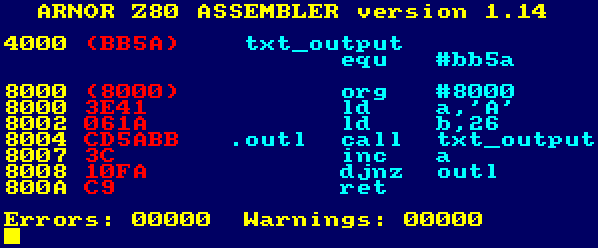

After trying to print some samples at the default resolution, I had no luck, so for reliability I halved the data density settings in the file optar.h:

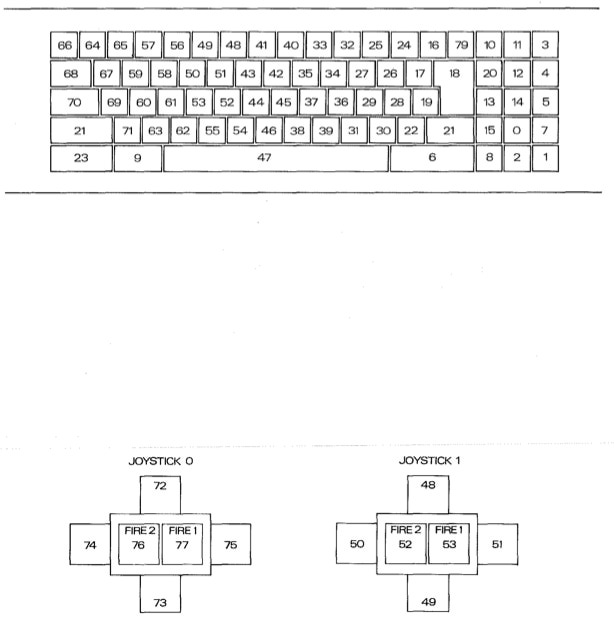

#define XCROSSES 33 /* Number of crosses horizontally */ #define YCROSSES 43 /* Number of crosses vertically */

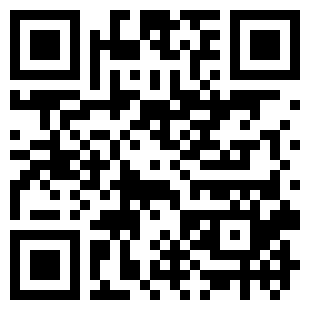

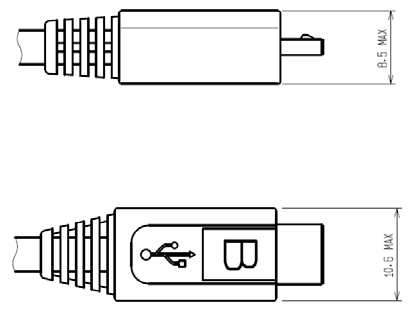

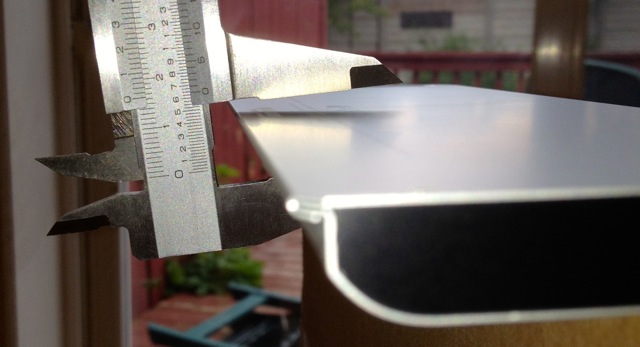

It’s quite important that your image prints and scans with a whole number of printer dots to image pixels. This used to be quite easy to do, before the advent of PDF’s “Scale to fit” misfeature, and also printer drivers that do a tonne of work in the background to “improve” the image. Add the mismatch between laser printer resolutions (300, 600, 1200 dpi …) and inkjets (360, 720, 1440 dpi …), and you’ve got lots of ways that this can go wrong.

Thankfully, there’s one common resolution that works across both types of printers. If you output the image at 120 dpi, that’s 5 laser printer dots at 600 dpi, or six inkjet dots at 720 dpi. And there was peace in the kingdom.

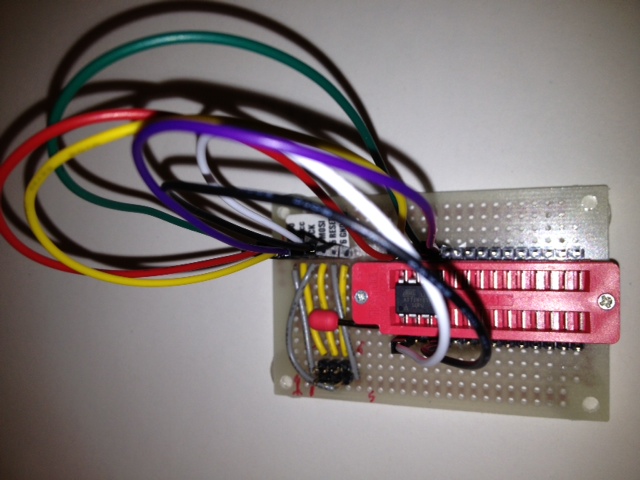

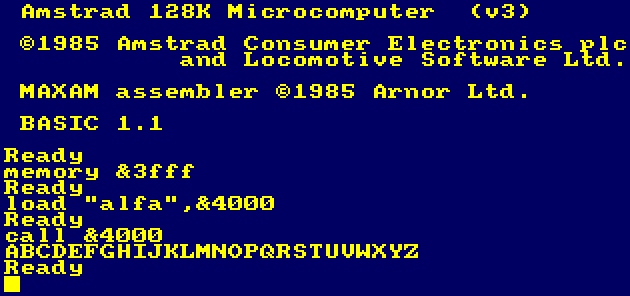

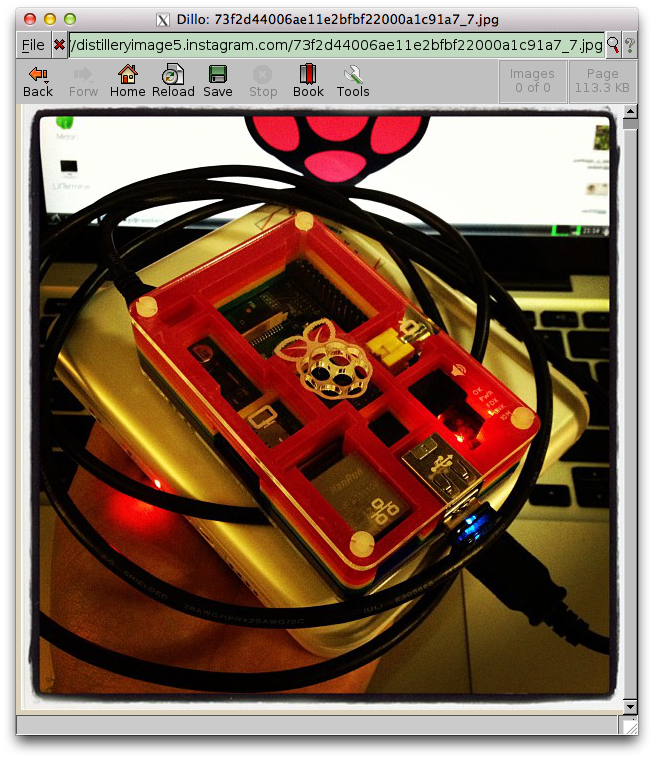

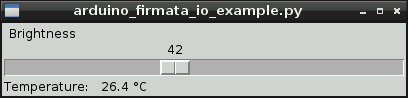

Here’s a demo, based on this:

So I took this track (which I used to have as a 7″, got at a jumble sale in the mid-70s) and converted it to a really low quality MPEG-2.5: MichelinJingle8kbit — that’s 175KB for just shy of three minutes of music (which, at this bitrate, sounds like it’s played through a layer of socks at the bottom of the Marianas Trench, but still).

Passing it through optar (which I wish wouldn’t produce PGM files; its output is mono) and bundling the pages into a PDF, I get this: optar_mj.pdf (760KB). Scanning that printout at 600dpi and running the pages through unoptar, I got this: optar1_mj.mp3. It’s the same as the input file, except padded with zeros at the end.

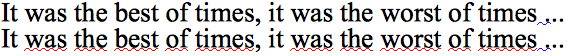

Sometimes, the scanning and conversion doesn’t do so well:

- mjoptar300dpi.mp3 — this is what happens when you scan at too low a resolution.

- mjx.mp3 — I have no idea what went wrong here, but: glitchtastic!