Back in 1973, the future definitely wasn’t equally distributed. While in Scotland we had power cuts, the looming three-day week and Miners’ Strike I, in California, the People’s Computer Company (PCC) was giving distributed computer access, teaching programming and publishing computer magazines. I don’t think we got that kind of access until (coincidentally) Miners’ Strike II a little over 10 years later.

But the People’s Computer Company magazine archive is a sunny thing, overfilled with joyful amateur enthusiasm and thousands of lines of code fit to make Edsger Dijkstra explode. Of course it was written for the local few who had access to mainframes and terminals, but it hardly seems to come from the same world as the dark evenings in Scotland spent cursing the smug neighbours’ house with all the lights on, their diesel generator putt-putting into the night.

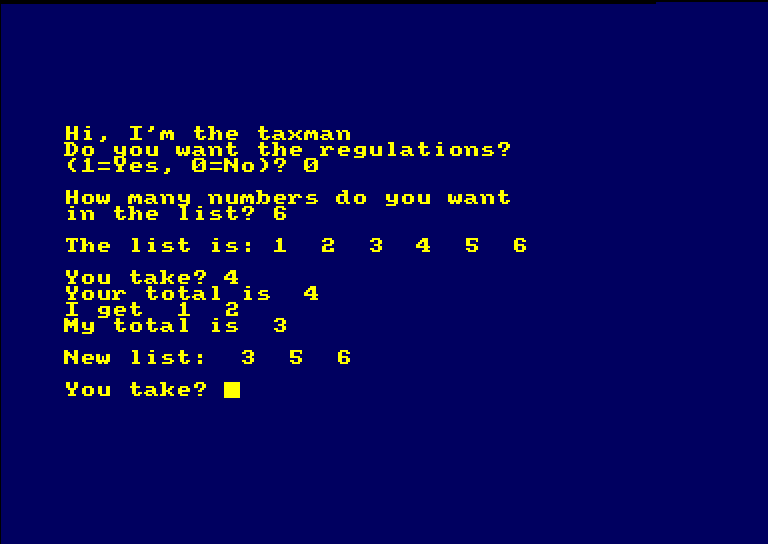

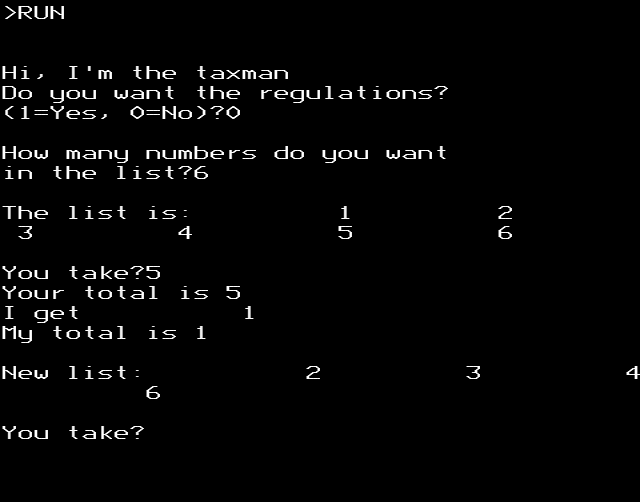

Lots of these games from the PCC era are forgettable now. The raw challenge of guessing a number on a text screen has paled somewhat in the face of 4K photo-realistic rendering. One game I found is still a little challenging, at least until you work out the trick of it: Taxman (or as the authors tried to rename it later, Factor Monster). Here’s a tiny sample game transcript:

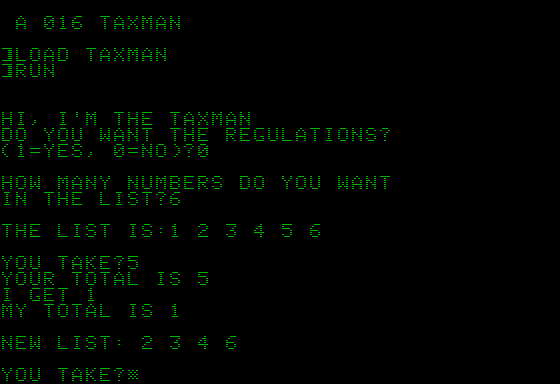

Hi, I'm the taxman Do you want the regulations? (1=Yes, 0=No)? 0 How many numbers do you want in the list? 6 The list is: 1 2 3 4 5 6 You take? 5 Your total is 5 I get 1 My total is 1 New list: 2 3 4 6 You take? 6 Your total is 11 I get 2 3 My total is 6 New list: 4 I get 4 because no factors of any number are left. My total is 10 You 11 Taxman 10 You win !!! Again (1=yes, 0=no)?

Seems I sneaked a lucky win there, but it’s harder than it looks. The rules are simple:

- Start with a list of consecutive numbers

- You choose a number, but it has to have some factors in the list

- The taxman (or the factor monster, a concept I much prefer as it doesn’t reinforce the Helmsley Doctrine) takes all the remaining factors of your number from the list

- You get to choose a number from the list, which is now missing your previous choice and all of its factors, and repeat

- Once the list has no multiples of any other number, the taxman/FM takes the rest

- The winner is whoever has the largest sum.

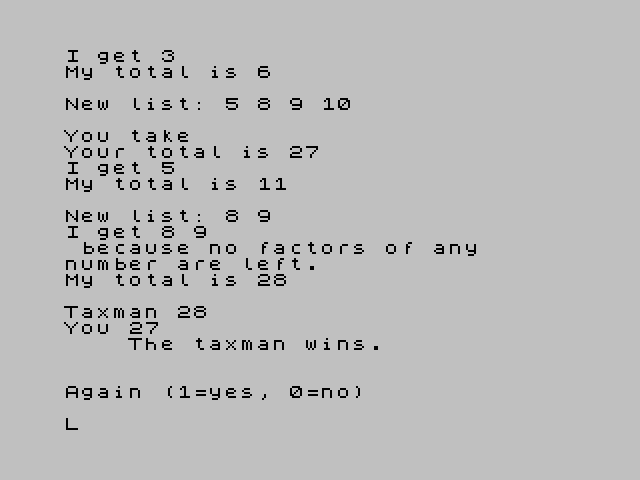

For such a simple game (or perhaps, such a simple me) the computer wins surprisingly often. Since I find it fun to play, I thought I’d share the 1973 love as much as possible by porting to all of the BASIC dialects that I knew.

Plain text BASIC – taxman.bas – runs under interpreters such as bas. Almost verbatim from the 1973 publication. May not allow you to play again on some interpreters; you might want to try my slightly rearranged 40 column version that should run on systems that don’t allow a variable to be dimensioned twice.

Amstrad CPC Locomotive BASIC – taxman.dsk – or as I call it, BASIC. 40 columns yellow on blue is how BASIC should look.

BBC BASIC – taxman.ssd – for all the boopBeep fans out there. You can actually play this one in your browser, too. Yes, the number formatting is weird, but BBC BASIC was always its own master.

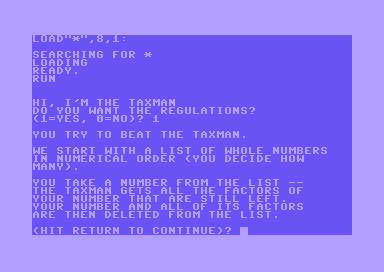

Commodore 64 – taxman.prg – very very upper case for this dinosaur of a BASIC.

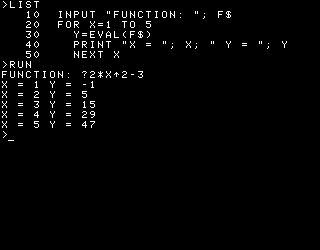

Apple II AppleSoft BASIC – TAXMAN.DSK – lots of fiddling with import tools and dialect weirdness because Apple.

ZX Spectrum (Sinclair BASIC) – taxman.tap – 32 columns plus a very special dialect (no END, GOTO and GOSUB are GO TO and GO SUB) meant this took a while, but it was quite rewarding to get going.

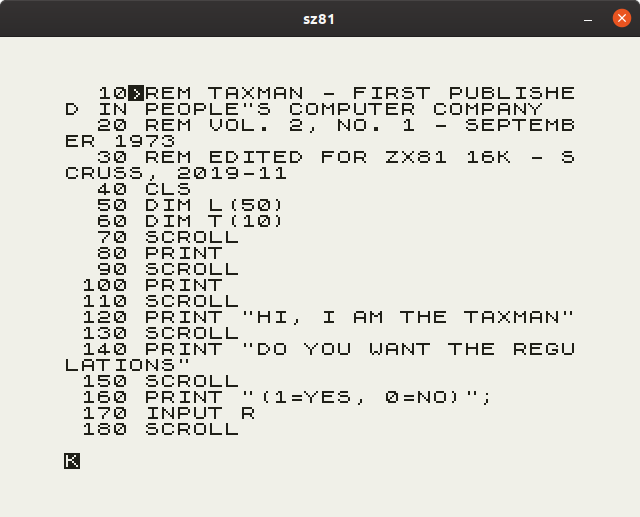

Sinclair ZX81 (16 K) – taxman.p – this one was a fight. The ZX81 didn’t scroll automatically, so you have to invoke SCROLL before every newline-generating PRINT or else your program will stop. For some reason this version gets unbearably slow near the end of long games, but it does complete.