Instagram filter used: Lo-fi

Photo taken at: Max’s Market

Artisanal Hardware Random Number Generator — scruss

(the Flickr page has popup notes about the circuit.)

Trickles out a few thousand made-with-love organic random numbers per second to the attached Arduino. The circuit is essentially Rob Seward’s True Random Number Generator v1 (after Will Ware, et al) which uses a MAX232 to power two reverse-biased 2N3904s to create avalanche noise. Another 2N3904 amplifies the resulting noise into something an Arduino can sample using AnalogRead(). Many modern processors include hardware RNGs (such as RdRand in recent Intel chipsets) so this circuit is just a toy now.

My interest in random number generators didn’t just arise from yesterday’s post. I’ve had various circuits breadboarded for months gathering dust, so I thought I’d pull out the most successful one and photograph it. Hardware RNGs seem to be a popular hobby electronics obsession, and there are many designs out there in variable states of “working†and/or “documentedâ€. I wanted one that could be powered from the 5V rail of an Arduino, and didn’t use too many expensive components. Rob’s RNG Version 2 circuit and code is the basis, but I replaced the 12V external supply with the MAX232 circuit he used in version 1.

Perhaps the reason that there are so many RNG projects out there in various states of abandonment is that making a good, reliable hardware RNG is hard. Just a few of the things you have to think about are:

(I’d like to thank Peter Todd for providing most of those issues over a pint and a chat during from a keysigning event. Peter saved me from spending too many hours working on this by hinting that — just maybe — I didn’t actually know what I was doing…)

If you want to read more on how to build a proper hardware RNG, the article “Understanding Intel’s Ivy Bridge Random Number Generator†and its references make a good (if very technical in places) introduction. I’m nowhere near paranoid enough to experiment further with RNG design, although I do have all the components to build an LM393-based XR232USB…

Uhoh. Wonder Pens sells pens — neato pens — and they are in Toronto. The Platinum Preppy they sent me free with my first order writes better than any $4 fountain pen should.

I’ve been at We Saw a Chicken … for 10 years now. From a tiny first post to now, it’s always been filed firmly under “misc.â€: no theme, no ads, no plan, and (until recently) no readers ☹

It’s been on two different hosts and two different platforms. It’s still obscurely named. It took a brief orange-carpeted journey into the 1970s. Dave‘s picture of a tiny bunny in my hands still gets more hits than I can believe. There was the whole WindSave thing, and the whole other pointless and ugly megabins thing. Then there was Raspberry Pi and The Quite Rubbish Clock; I got more hits in a week than I got in the previous nine years.

For reasons too annoying to explain, my GnuPG keyring was huge. It was taking a long time to find keys, and most of them weren’t ones I’d use. So I wrote this little script that strips out all of the keys that aren’t

The script doesn’t actually delete any keys. It produces shell-compatible output that you can pipe or copy to a shell. Now my keyring file is less than 4% the size (or more precisely, 37‰) of the size it was before.

#!/bin/bash

# clean_keyring.sh - clean up all the excess keys

# my key should probably be the first secret key listed

mykey=$(gpg --list-secret-keys | grep '^sec' | cut -c 13-20 | head -1)

if

[ -z $mykey ]

then

# exit if no key string

echo "Can't get user's key ID"

exit 1

fi

# all of the people who have signed my key

mysigners=$(gpg --list-sigs $mykey | grep '^sig' | cut -c 14-21 | sort -u)

# keep all of the signers, plus my key (if I haven't self-signed)

keepers=$(echo $mykey $mysigners | tr ' ' '\012' | sort -u)

# the keepers list in egrep syntax: ^(key|key|…)

keepers_egrep=$(echo $keepers | sed 's/^/^(/; s/$/)/; s/ /|/g;')

# show all the keepers as a comment so this script's output is shell-able

echo '# Keepers: ' $keepers

# everyone who isn't on the keepers list is deleted

deleters=$(gpg --list-keys | grep '^pub'| cut -c 13-20 | egrep -v ${keepers_egrep})

# echo the command if there are any to delete

# command is interactive

if

[ -z $deleters ]

then

echo "# Nothing to delete!"

else

echo 'gpg --delete-keys' $deleters

fi

Files:

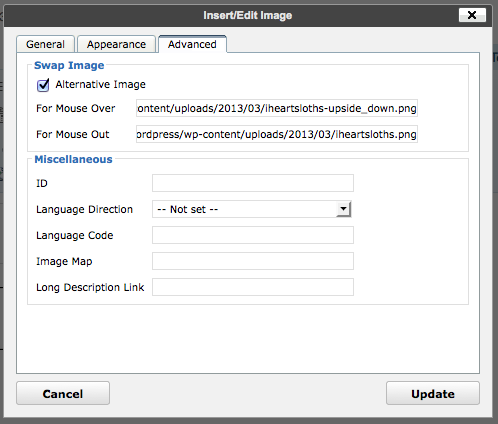

![]() Probably best to retire my ad hoc image rollover in wordpress, as Ultimate TinyMCE has it covered. Sure, it’s a plugin, but it makes it so much easier. After uploading your two images, select an image and put the two URLs into the Mouse Over/Out fields:

Probably best to retire my ad hoc image rollover in wordpress, as Ultimate TinyMCE has it covered. Sure, it’s a plugin, but it makes it so much easier. After uploading your two images, select an image and put the two URLs into the Mouse Over/Out fields:

Easy! And no digging into the page source, either.

I really never though I’d see this happen, but The Complete Uncle really looks like it’s going to get published.