From the box of the rather excellent Creality Ender 3 3d printer I just bought from Digitmakers.

Instagram filter used: Normal

From the box of the rather excellent Creality Ender 3 3d printer I just bought from Digitmakers.

Instagram filter used: Normal

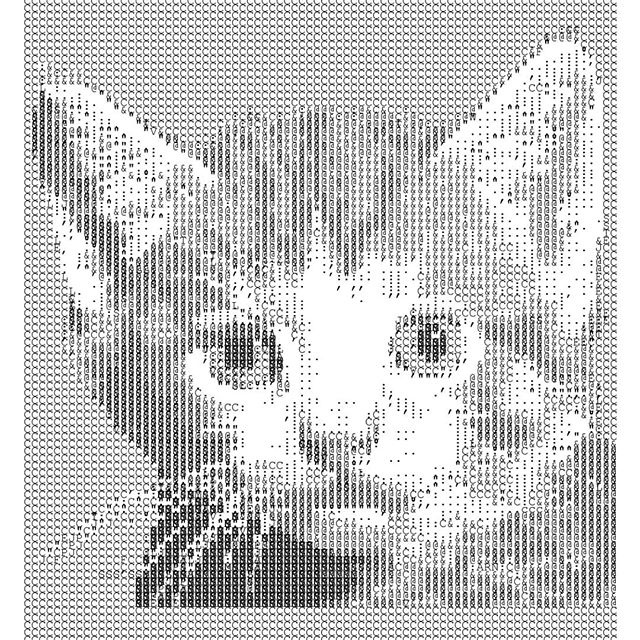

From Nick Higham’s note on Typewriter Art, referring to Bob Neill’s Book of Typewriter Art (with special computer program). Nick wrote the special program back in the early 1980s. What I did to get this output:

Bob Neill’s art relies on being able to set a typewriter’s vertical advance to the same value as its horizontal one, and also being able to overprint lines to get darker results. The results are pretty good: tabby.pdf

Instagram filter used: Normal

3d files here — egg.zip — or get them on Thingiverse: Egg by scruss – Thingiverse

Instagram filter used: Normal

I just got brian d. foy’s Learning Perl 6 from the library. It’s a pretty good book, though it’ll take a good few readings for some of Perl 6’s features to stick.

Since Perl 6 is built using Unicode from the ground up, it does two rather wonderful things when dealing with numbers:

So herewith a table (probably incomplete, and very unlikely to render properly for you) of Unicode glyphs accepted by Perl 6 as numeric values:

| Value | Glyphs |

|---|---|

| -0.5 | ༳ |

| 0 | 0 Ù Û° ߀ ० ০ ੦ ૦ ঠ௦ ౦ ౸ ೦ ൦ ๠໠༠ဠႠ០៰ á ᥆ ᧠᪀ ᪠á á®° á±€ á± â° â‚€ ↉ ⓪ â“¿ 〇 ê˜ ê›¯ ê£ ê¤€ ê§ ê© ê¯° ï¼ ð†Š ð’ 𑦠𑃰 𑄶 𑇠𑛀 🎠😠🢠🬠🶠🄀 🄠|

| 0.0625 | ৴ àµ ê ³ |

| 0.1 | â…’ |

| 0.111111 | â…‘ |

| 0.125 | ৵ ච⅛ ê ´ ð’‘Ÿ |

| 0.142857 | â… |

| 0.166667 | â…™ ð’‘¡ |

| 0.1875 | ৶ à· ê µ |

| 0.2 | â…• |

| 0.25 | ¼ ৷ ಠ൳ ê ° ð…€ ð¹¼ ð’‘ ð’‘¢ |

| 0.333333 | â…“ ð¹½ ð’‘š ð’‘ |

| 0.375 | ⅜ |

| 0.4 | â…– |

| 0.5 | ½ ೠ൴ ༪ â³½ ê ± ð… ð…µ ð…¶ ð¹» |

| 0.6 | â…— |

| 0.625 | â… |

| 0.666667 | â…” ð…· ð¹¾ ð’‘› ð’‘ž |

| 0.75 | ¾ ৸ ഠ൵ ê ² ð…¸ |

| 0.8 | â…˜ |

| 0.833333 | ⅚ 𒑜 |

| 0.875 | â…ž |

| 1 | 1 ¹ Ù¡ Û± ß à¥§ ১ ੧ ૧ ৠ௧ ౧ à±¹ à±¼ ೧ ൧ ๑ ໑ ༡ á á‚‘ ᩠១ ៱ á ‘ ᥇ ᧑ ᧚ ᪠᪑ á‘ á®± ᱠ᱑ â‚ â…Ÿ â… â…° â‘ â‘´ â’ˆ ⓵ ⶠ➀ ➊ 〡 ㆒ ㈠㊀ ꘡ ꛦ ꣑ ê¤ ê§‘ ê©‘ ꯱ 1 ð„‡ ð…‚ ð…˜ ð…™ ð…š ðŒ ð‘ 𒡠𡘠𤖠𩀠𩽠ð˜ ð¸ ð¹ 𑒠𑧠𑃱 ð‘„· 𑇑 𑛠𒕠𒞠𒬠𒴠𒑠𒑘 ð ðŸ 🙠🣠ðŸ 🷠🄂 |

| 1.5 | ༫ |

| 2 | 2 ² Ù¢ Û² ß‚ २ ২ ੨ ૨ ਠ௨ ౨ ౺ à±½ ೨ ൨ ๒ à»’ ༢ á‚ á‚’ ᪠២ ៲ á ’ ᥈ ᧒ ᪂ ᪒ ᒠ᮲ ᱂ á±’ â‚‚ â…¡ â…± â‘¡ ⑵ â’‰ ⓶ â· âž âž‹ 〢 ㆓ ㈡ ㊠꘢ ꛧ ꣒ ꤂ ꧒ ê©’ ꯲ ï¼’ ð„ˆ ð…› ð…œ ð… ð…ž ð’ 𒢠𡙠𤚠ð© ð™ ð¹ 𹡠𑓠𑨠𑃲 𑄸 𑇒 ð‘›‚ ð’€ ð’– ð’Ÿ ð’£ ð’ ð’µ ð’‘Š ð’‘ ð’‘– ð’‘™ ð¡ ðŸ 🚠🤠🮠🸠🄃 |

| 2.5 | ༬ |

| 3 | 3 ³ Ù£ Û³ ߃ ३ ৩ à©© à«© ੠௩ ౩ à±» à±¾ ೩ ൩ ๓ ໓ ༣ რ႓ ᫠៣ ៳ á “ ᥉ ᧓ ᪃ ᪓ ᓠ᮳ ᱃ ᱓ ₃ â…¢ â…² â‘¢ ⑶ â’Š â“· ⸠➂ ➌ 〣 ㆔ ㈢ ㊂ ꘣ ꛨ ꣓ ꤃ ꧓ ê©“ ꯳ 3 ð„‰ ð’£ ð¡š ð¤› ð©‚ ðš ðº 𹢠𑔠𑩠𑃳 ð‘„¹ 𑇓 𑛃 ð’ ð’ˆ ð’— ð’ ð’¤ ð’¥ ð’® ð’¯ ð’¶ ð’· ð’º ð’» ð’‘‹ ð’‘‘ ð’‘— ð¢ 👠🛠🥠🯠🹠🄄 |

| 3.141592653589793 | π |

| 3.5 | ༠|

| 4 | 4 Ù¤ Û´ ß„ ४ ৪ ੪ ૪ ઠ௪ ౪ ೪ ൪ ๔ à»” ༤ á„ á‚” ᬠ៤ ៴ á ” ᥊ ᧔ ᪄ ᪔ á” á®´ ᱄ á±” â´ â‚„ â…£ â…³ â‘£ â‘· â’‹ ⓸ ⹠➃ ➠〤 ㆕ ㈣ ㊃ ꘤ ꛩ ꣔ ꤄ ꧔ ê©” ꯴ ï¼” ð„Š ð’¤ ð©ƒ ð› ð» 𹣠𑕠𑪠𑃴 𑄺 𑇔 ð‘›„ ð’‚ ð’‰ ð’ ð’˜ ð’¡ ð’¦ ð’° ð’¸ ð’¼ ð’½ ð’¾ ð’¿ ð’‘Œ ð’‘’ ð’‘“ ð£ 💠🜠🦠🰠🺠🄅 |

| 4.5 | ༮ |

| 5 | 5 Ù¥ Ûµ ß… ५ ৫ à©« à«« ૠ௫ ౫ ೫ ൫ ๕ ໕ ༥ á… á‚• á ៥ ៵ á • ᥋ ᧕ ᪅ ᪕ ᕠ᮵ á±… ᱕ âµ â‚… â…¤ â…´ ⑤ ⑸ â’Œ ⓹ ⺠➄ ➎ 〥 ㈤ ㊄ ꘥ ꛪ ꣕ ꤅ ꧕ ê©• ꯵ 5 ð„‹ ð…ƒ ð…ˆ ð… ð…Ÿ ð…³ ðŒ¡ ð’¥ ð¹¤ ð‘– ð‘« ð‘ƒµ ð‘„» 𑇕 ð‘›… ð’ƒ ð’Š ð’ ð’™ ð’¢ ð’§ ð’± ð’¹ ð’‘ ð’‘” ð’‘• ð¤ 📠ðŸ 🧠🱠🻠🄆 |

| 5.5 | ༯ |

| 6 | 6 Ù¦ Û¶ ߆ ६ ৬ ੬ ૬ ଠ௬ ౬ ೬ ൬ ๖ à»– ༦ ᆠ႖ ᮠ៦ ៶ á – ᥌ ᧖ ᪆ ᪖ ᖠ᮶ ᱆ á±– ⶠ₆ â…¥ â…µ ↅ â‘¥ ⑹ ⒠⓺ â» âž… ➠〦 ㈥ ㊅ ꘦ ꛫ ꣖ ꤆ ꧖ ê©– ꯶ ï¼– ð„Œ ð’¦ ð¹¥ ð‘— ð‘¬ ð‘ƒ¶ ð‘„¼ 𑇖 𑛆 ð’„ ð’‹ ð’‘ ð’š ð’¨ ð’‘€ ð’‘Ž ð¥ 🔠🞠🨠🲠🼠🄇 |

| 6.5 | ༰ |

| 7 | 7 Ù§ Û· ߇ ॠৠ੠ૠà ௠ౠೠൠ๗ à»— ༧ ᇠ႗ ᯠ៧ ៷ á — ᥠ᧗ ᪇ ᪗ á— á®· ᱇ á±— ⷠ₇ â…¦ â…¶ ⑦ ⑺ â’Ž â“» ⼠➆ ➠〧 ㈦ ㊆ ꘧ ꛬ ꣗ ꤇ ꧗ ê©— ꯷ ï¼— ð„ 𒧠𹦠𑘠ð‘ 𑃷 ð‘„½ 𑇗 𑛇 𒅠𒌠𒒠𒛠𒩠𒑠𒑂 𒑃 ð¦ 🕠🟠🩠🳠🽠🄈 |

| 7.5 | ༱ |

| 8 | 8 Ù¨ Û¸ ߈ ८ ৮ à©® à«® ஠௮ à±® à³® ൮ ๘ ໘ ༨ ሠ႘ ᰠ៨ ៸ á ˜ ᥎ ᧘ ᪈ ᪘ ᘠ᮸ ᱈ ᱘ ⸠₈ â…§ â…· ⑧ â‘» ⒠⓼ ⽠➇ âž‘ 〨 ㈧ ㊇ ꘨ ê› ê£˜ ꤈ ꧘ ꩘ ꯸ 8 ð„Ž ð’¨ ð¹§ ð‘™ ð‘® ð‘ƒ¸ ð‘„¾ 𑇘 𑛈 ð’† ð’ 𒓠𒜠𒪠𒑄 ð’‘… ð§ 🖠ðŸ 🪠🴠🾠🄉 |

| 8.5 | ༲ |

| 9 | 9 Ù© Û¹ ߉ ९ ৯ ੯ ૯ ௠௯ ౯ ೯ ൯ ๙ à»™ ༩ በ႙ ᱠ៩ ៹ á ™ ᥠ᧙ ᪉ ᪙ ᙠ᮹ ᱉ á±™ ⹠₉ â…¨ â…¸ ⑨ ⑼ ⒠⓽ ⾠➈ âž’ 〩 ㈨ ㊈ ꘩ ê›® ꣙ ꤉ ꧙ ê©™ ꯹ ï¼™ ð„ 𒩠𹨠𑚠𑯠𑃹 ð‘„¿ 𑇙 𑛉 ð’‡ ð’Ž ð’” ð’ 𒫠𒑆 𒑇 𒑈 𒑉 ð¨ 🗠🡠🫠🵠🿠🄊 |

| 10 | ௰ ൰ á² â…© â…¹ â‘© ⑽ â’‘ ⓾ ⿠➉ âž“ 〸 ㈩ ㉈ ㊉ ð„ ð…‰ ð… ð…— ð… ð…¡ ð…¢ ð…£ ð…¤ ðŒ¢ ð“ 𡛠𤗠𩄠ðœ ð¼ 𹩠𑛠ð© |

| 11 | Ⅺ ⅺ ⑪ ⑾ ⒒ ⓫ |

| 12 | Ⅻ ⅻ ⑫ ⑿ ⒓ ⓬ |

| 13 | ⑬ ⒀ ⒔ ⓠ|

| 14 | â‘ â’ â’• â“® |

| 15 | ⑮ ⒂ ⒖ ⓯ |

| 16 | ৹ ⑯ ⒃ ⒗ ⓰ |

| 17 | ᛮ ⑰ ⒄ ⒘ ⓱ |

| 18 | ᛯ ⑱ ⒅ ⒙ ⓲ |

| 19 | ᛰ ⑲ ⒆ ⒚ ⓳ |

| 20 | ᳠⑳ â’‡ â’› â“´ 〹 ㉉ ð„‘ ð” 𡜠𤘠𩅠ð ð½ 𹪠𑜠ðª |

| 21 | ㉑ |

| 22 | ㉒ |

| 23 | ㉓ |

| 24 | ㉔ |

| 25 | ㉕ |

| 26 | ㉖ |

| 27 | ㉗ |

| 28 | ㉘ |

| 29 | ㉙ |

| 30 | ᴠ〺 ㉊ ㉚ ð„’ ð…¥ ð¹« ð‘ ð« |

| 31 | ㉛ |

| 32 | ㉜ |

| 33 | ㉠|

| 34 | ㉞ |

| 35 | ㉟ |

| 36 | ㊱ |

| 37 | ㊲ |

| 38 | ㊳ |

| 39 | ㊴ |

| 40 | ᵠ㉋ ㊵ ð„“ ð¹¬ ð‘ž ð¬ |

| 41 | ㊶ |

| 42 | ㊷ |

| 43 | ㊸ |

| 44 | ㊹ |

| 45 | ㊺ |

| 46 | ㊻ |

| 47 | ㊼ |

| 48 | ㊽ |

| 49 | ㊾ |

| 50 | ᶠⅬ â…¼ ↆ ㉌ ㊿ ð„” ð…„ ð…Š ð…‘ ð…¦ ð…§ ð…¨ ð…© ð…´ ðŒ£ ð©¾ ð¹ ð‘Ÿ ð |

| 60 | á· ã‰ ð„• ð¹® ð‘ ð® |

| 70 | Ḡ㉎ ð„– ð¹¯ ð‘¡ ð¯ |

| 80 | á¹ ã‰ ð„— ð¹° ð‘¢ ð° |

| 90 | áº ð„˜ ð ð¹± ð‘£ ð± |

| 100 | ௱ ൱ á» â… â…½ ð„™ ð…‹ ð…’ ð…ª ð• ð¡ 𤙠𩆠ðž ð¾ 𹲠𑤠|

| 200 | ð„š ð¹³ |

| 300 | ð„› ð…« ð¹´ |

| 400 | ð„œ ð¹µ |

| 500 | â…® â…¾ ð„ ð…… ð…Œ ð…“ ð…¬ ð… ð…® ð…¯ ð…° ð¹¶ |

| 600 | ð„ž ð¹· |

| 700 | ð„Ÿ ð¹¸ |

| 800 | ð„ ð¹¹ |

| 900 | ð„¡ ðŠ 𹺠|

| 1000 | ௲ ൲ â…¯ â…¿ ↀ ð„¢ ð… ð…” ð…± ð¡ž ð©‡ ðŸ ð¿ ð‘¥ |

| 2000 | ð„£ |

| 3000 | ð„¤ |

| 4000 | ð„¥ |

| 5000 | â† ð„¦ ð…† ð…Ž ð…² |

| 6000 | ð„§ |

| 7000 | ð„¨ |

| 8000 | ð„© |

| 9000 | ð„ª |

| 10000 | ἠↂ ð„« ð…• ð¡Ÿ |

| 20000 | ð„¬ |

| 30000 | ð„ |

| 40000 | ð„® |

| 50000 | ↇ ð„¯ ð…‡ ð…– |

| 60000 | ð„° |

| 70000 | ð„± |

| 80000 | ð„² |

| 90000 | ð„³ |

| 100000 | ↈ |

| 216000 | ð’² |

| 432000 | ð’³ |

| Inf | ∞ |

So the title of this post really is accepted as a valid Perl 6 expression in the REPL:

$ perl6 To exit type 'exit' or '^D' > ð’³ / ༳ == ( ⑽ - ð¹ ) * ( ð’² / ð…‰ ) True

What does it evaluate to? Well:

Definitely into just because you can doesn’t mean you should territory, and a feature to make the Pythonistas reach for the Zantac again, poor dears.

Just started on a SBC6120 RBC Edition kit. It’s a DEC PDP-8-compatible single board computer that uses a CMOS chipset from the early 1980s. Yes, it will be very slow, even with the optional speedy 8 MHz oscillator installed. With a 12-bit processor and 32 kilo-words of RAM, this is definitely going to be a Slow Computing device.

Lots and lots of sockets. So many sockets. It’s quite soothing soldering them all in, one hole at a time. It looks like it’ll go more quickly than the Zeta did.

> Does anyone know what each of the pins on the 6502 CPU chip in the Apple II Plus does?

They all plug into the socket on the motherboard to keep the chip from drifting away. – c.s.a2 FAQ of yore

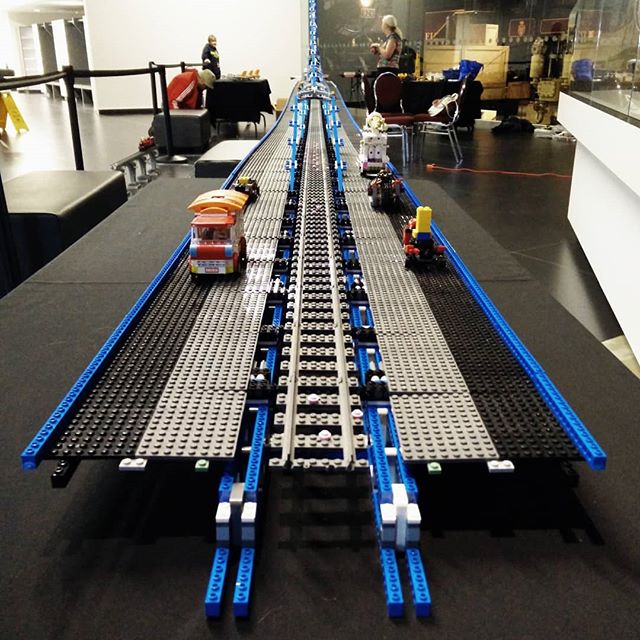

Instagram filter used: Normal

Photo taken at: Canada Science and Technology Museum