Instagram filter used: Normal

Blog

-

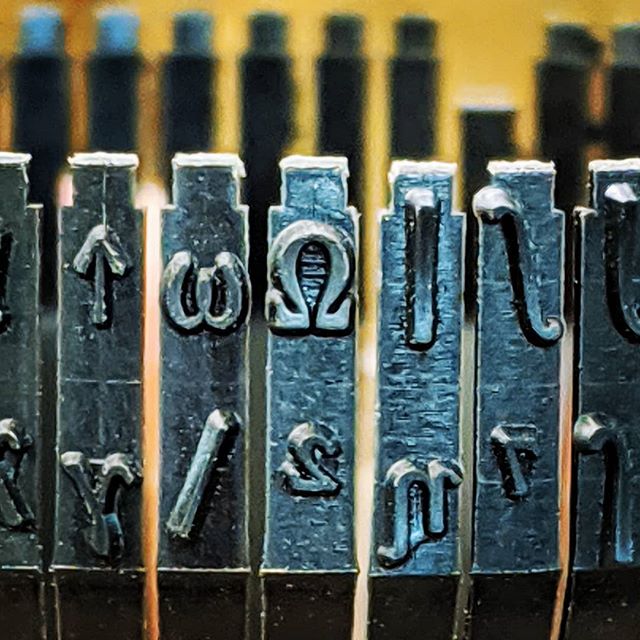

The coolest font (when I was 15, that is)

The Colossal Cave font on the Amstrad CPC 464 Though I didn’t really have the patience for text adventures, Level 9 used what I thought was the coolest font (circa 1985). After checking through them all on the Internet Archive Amstrad CPC software library, I couldn’t find a version that used this bitmap font. I eventually found it on nvg. After lots of messing about, I extracted it and present it here. I’m sure I’ll make a TTF of it soon enough.

Tastes change a bit, don’t they?

10 REM *** L9FONT.BAS *** 15 REM bitmap font from Level 9's 20 REM Colossal Cave adventure 30 REM on the Amstrad CPC 464 40 REM (it was so cool at the time…) 50 REM Dug up by scruss, 2019-12 60 REM ============================== 100 SYMBOL AFTER 32 110 MODE 1 120 GOSUB 1000 130 PRINT" *** It's the Level 9 font ***" 140 PRINT" *** from Colossal Cave! ***" 150 PRINT" Dug up by scruss, 2019-12" 160 PRINT 170 PEN 2 180 PRINT"Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur" 190 PRINT"adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor" 200 PRINT"incididunt ut labore et dolore magna" 210 PRINT"aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis" 220 PRINT"nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris" 230 PRINT"nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat" 240 PRINT"arfle barfle gloop? | | |" 250 PRINT 260 PEN 1 270 FOR i%=32 TO 127 280 PRINT CHR$(i%); " "; 290 NEXT i% 300 PRINT 310 PRINT 990 END 1000 SYMBOL 33,&18,&24,&24,&24,&18,&0,&18,&0 1010 SYMBOL 34,&66,&66,&44,&88,&0,&0,&0,&0 1020 SYMBOL 35,&0,&24,&7E,&24,&24,&7E,&24,&0 1030 SYMBOL 36,&12,&7C,&D0,&7C,&16,&FC,&10,&0 1040 SYMBOL 37,&E4,&A4,&E8,&10,&2E,&4A,&4E,&0 1050 SYMBOL 38,&70,&D8,&D8,&72,&D6,&CC,&76,&0 1060 SYMBOL 39,&30,&30,&20,&40,&0,&0,&0,&0 1070 SYMBOL 40,&1C,&38,&70,&70,&70,&38,&1C,&0 1080 SYMBOL 41,&70,&38,&1C,&1C,&1C,&38,&70,&0 1090 SYMBOL 42,&10,&54,&38,&FE,&38,&54,&10,&0 1100 SYMBOL 43,&0,&10,&10,&7C,&10,&10,&0,&0 1110 SYMBOL 44,&0,&0,&0,&0,&30,&30,&20,&40 1120 SYMBOL 45,&0,&0,&0,&F8,&0,&0,&0,&0 1130 SYMBOL 46,&0,&0,&0,&0,&0,&60,&60,&0 1140 SYMBOL 47,&0,&4,&8,&10,&20,&40,&0,&0 1150 SYMBOL 48,&7C,&C6,&CE,&D6,&E6,&C6,&7C,&0 1160 SYMBOL 49,&8,&18,&38,&18,&18,&18,&3C,&0 1170 SYMBOL 50,&3C,&66,&C,&18,&30,&62,&7E,&0 1180 SYMBOL 51,&7E,&4C,&18,&3C,&6,&66,&3C,&0 1190 SYMBOL 52,&4,&C,&1C,&2C,&7E,&C,&1E,&0 1200 SYMBOL 53,&3E,&66,&60,&7C,&6,&6,&7C,&0 1210 SYMBOL 54,&3C,&66,&60,&7C,&66,&66,&3C,&0 1220 SYMBOL 55,&7E,&46,&6,&C,&C,&18,&18,&0 1230 SYMBOL 56,&3C,&66,&34,&18,&2C,&66,&3C,&0 1240 SYMBOL 57,&3C,&66,&66,&3E,&6,&66,&3C,&0 1250 SYMBOL 58,&0,&30,&30,&0,&0,&30,&30,&0 1260 SYMBOL 59,&0,&30,&30,&0,&30,&30,&20,&40 1270 SYMBOL 60,&1C,&30,&60,&C0,&60,&30,&1C,&0 1280 SYMBOL 61,&0,&0,&F8,&0,&F8,&0,&0,&0 1290 SYMBOL 62,&E0,&30,&18,&C,&18,&30,&E0,&0 1300 SYMBOL 63,&7C,&64,&C,&18,&10,&0,&10,&0 1310 SYMBOL 64,&7C,&C6,&DE,&D2,&DE,&C0,&7E,&0 1320 SYMBOL 65,&18,&6C,&C6,&C6,&FE,&66,&F6,&0 1330 SYMBOL 66,&FC,&C6,&C6,&FC,&C6,&C6,&FC,&0 1340 SYMBOL 67,&3C,&66,&C0,&C0,&C0,&66,&3C,&0 1350 SYMBOL 68,&D8,&EC,&C6,&C6,&C6,&EC,&D8,&0 1360 SYMBOL 69,&FE,&62,&60,&78,&60,&62,&FE,&0 1370 SYMBOL 70,&FE,&62,&60,&78,&60,&60,&E0,&0 1380 SYMBOL 71,&3C,&66,&C0,&CE,&C6,&66,&3C,&0 1390 SYMBOL 72,&C6,&C6,&C6,&FE,&C6,&C6,&C6,&0 1400 SYMBOL 73,&7E,&18,&18,&18,&18,&18,&7E,&0 1410 SYMBOL 74,&FE,&8C,&C,&C,&C,&CC,&78,&0 1420 SYMBOL 75,&E6,&CC,&D8,&F0,&D8,&CC,&C6,&0 1430 SYMBOL 76,&E0,&C0,&C0,&C0,&C0,&C2,&FE,&0 1440 SYMBOL 77,&C6,&EE,&FE,&D6,&C6,&C6,&CC,&0 1450 SYMBOL 78,&CE,&E6,&F6,&DE,&CE,&C6,&C6,&0 1460 SYMBOL 79,&38,&6C,&C6,&C6,&C6,&6C,&38,&0 1470 SYMBOL 80,&DC,&E6,&C6,&C6,&FC,&C0,&C0,&0 1480 SYMBOL 81,&38,&6C,&C6,&C6,&CA,&64,&3A,&0 1490 SYMBOL 82,&DC,&E6,&C6,&C6,&FC,&CC,&C6,&0 1500 SYMBOL 83,&7C,&C6,&C0,&7C,&6,&C6,&7C,&0 1510 SYMBOL 84,&FE,&B2,&30,&30,&30,&30,&30,&0 1520 SYMBOL 85,&E6,&66,&C6,&C6,&C6,&C6,&7C,&0 1530 SYMBOL 86,&E6,&66,&C6,&C6,&CC,&78,&30,&0 1540 SYMBOL 87,&EC,&66,&C6,&C6,&D6,&D6,&6C,&0 1550 SYMBOL 88,&EE,&C6,&6C,&38,&6C,&C6,&EE,&0 1560 SYMBOL 89,&EE,&C6,&2C,&18,&18,&18,&18,&0 1570 SYMBOL 90,&FE,&8C,&18,&30,&60,&C2,&FE,&0 1580 SYMBOL 91,&7C,&64,&60,&60,&60,&60,&7C,&0 1590 SYMBOL 92,&0,&60,&30,&10,&8,&C,&6,&0 1600 SYMBOL 93,&3E,&6,&6,&6,&6,&26,&3E,&0 1610 SYMBOL 94,&18,&24,&42,&42,&0,&0,&0,&0 1620 SYMBOL 95,&0,&0,&0,&0,&0,&0,&EE,&BB 1630 SYMBOL 96,&3C,&22,&78,&20,&78,&20,&7E,&0 1640 SYMBOL 97,&0,&0,&74,&DC,&C4,&CC,&74,&0 1650 SYMBOL 98,&C0,&C0,&DC,&E6,&C6,&E6,&DC,&0 1660 SYMBOL 99,&0,&0,&78,&CC,&C0,&CC,&78,&0 1670 SYMBOL 100,&0,&70,&18,&7C,&CC,&CC,&78,&0 1680 SYMBOL 101,&0,&0,&78,&CC,&FC,&C0,&7C,&0 1690 SYMBOL 102,&68,&74,&60,&F8,&60,&60,&60,&C0 1700 SYMBOL 103,&0,&0,&78,&CC,&C0,&CC,&7C,&C 1710 SYMBOL 104,&C0,&C0,&D8,&EC,&CC,&D8,&DC,&0 1720 SYMBOL 105,&C,&0,&38,&18,&18,&18,&38,&0 1730 SYMBOL 106,&6,&0,&1C,&C,&C,&C,&4C,&38 1740 SYMBOL 107,&C0,&C0,&CC,&D8,&F0,&D8,&CE,&0 1750 SYMBOL 108,&30,&30,&30,&30,&30,&36,&3E,&0 1760 SYMBOL 109,&0,&0,&AC,&D6,&D6,&C6,&CC,&0 1770 SYMBOL 110,&0,&0,&BC,&C6,&C6,&CC,&DE,&0 1780 SYMBOL 111,&0,&0,&7C,&C6,&C6,&C6,&7C,&0 1790 SYMBOL 112,&0,&0,&DC,&E6,&C6,&E6,&DC,&C0 1800 SYMBOL 113,&0,&0,&76,&CE,&C6,&CE,&76,&6 1810 SYMBOL 114,&0,&0,&DC,&E6,&C6,&FC,&C6,&0 1820 SYMBOL 115,&0,&0,&3C,&60,&3C,&8E,&7C,&0 1830 SYMBOL 116,&18,&30,&FC,&30,&30,&32,&1C,&0 1840 SYMBOL 117,&0,&0,&E6,&66,&C6,&C6,&7A,&0 1850 SYMBOL 118,&0,&0,&EC,&66,&C6,&EC,&38,&0 1860 SYMBOL 119,&0,&0,&EC,&C6,&D2,&7C,&28,&0 1870 SYMBOL 120,&0,&0,&EE,&6C,&38,&6C,&EE,&0 1880 SYMBOL 121,&0,&0,&EC,&C6,&6C,&18,&30,&E0 1890 SYMBOL 122,&0,&0,&FE,&9C,&30,&62,&FE,&0 1900 SYMBOL 123,&C,&30,&30,&60,&30,&30,&C,&0 1910 SYMBOL 124,&CF,&DB,&DB,&CF,&C3,&DB,&FB,&0 1920 SYMBOL 125,&60,&18,&18,&C,&18,&18,&60,&0 1930 SYMBOL 126,&7C,&C6,&BA,&A2,&BA,&C6,&7C,&0 1940 SYMBOL 127,&FF,&FF,&FF,&FF,&FF,&FF,&FF,&FF 1950 RETURN

-

Save money, buy misery: cheap STM32 boards

(I’m still writing this. It will change over time.)

“Use an STM32 Blue Pill or Black Pill micro-controller boardâ€, they said. “So cheap, so powerfulâ€, they said. “You’ll love itâ€, they said.

Dear Reader, none of the above turned out to be true.

For some time now I’ve been looking for a cheap, USB HID micro-controller board that is somewhat more flexible than the ATMega32U4 (Arduinos Leonardo, Micro and Pro Micro; also the impossibly smol Atto) and yet not quite as flexible as the let’s-accidentally-overwrite-our-accessibility-code-with-the-holiday-snaps CircuitPython boards from Adafruit. And for a while it looked like the STM32 boards might do it: they’ve got a 72 MHz ARM Cortex-M3 with at least 64 KB of Flash and 20 KB of SRAM and they’re under $5. Yay?

Not quite. There are three main problems with the STM32 boards that get in the way of inexpensive electronic nerdery.

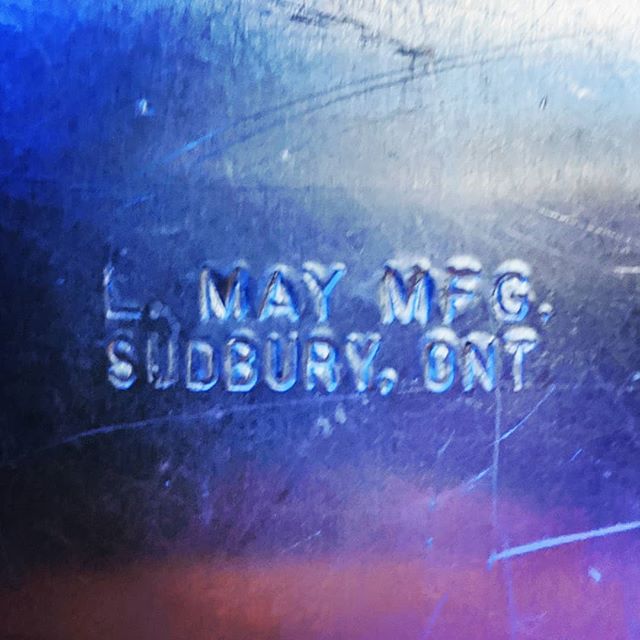

1: They may not actually be STM32 chips

Slightly grotty photos follow. One day I’ll get a better USB microscope.

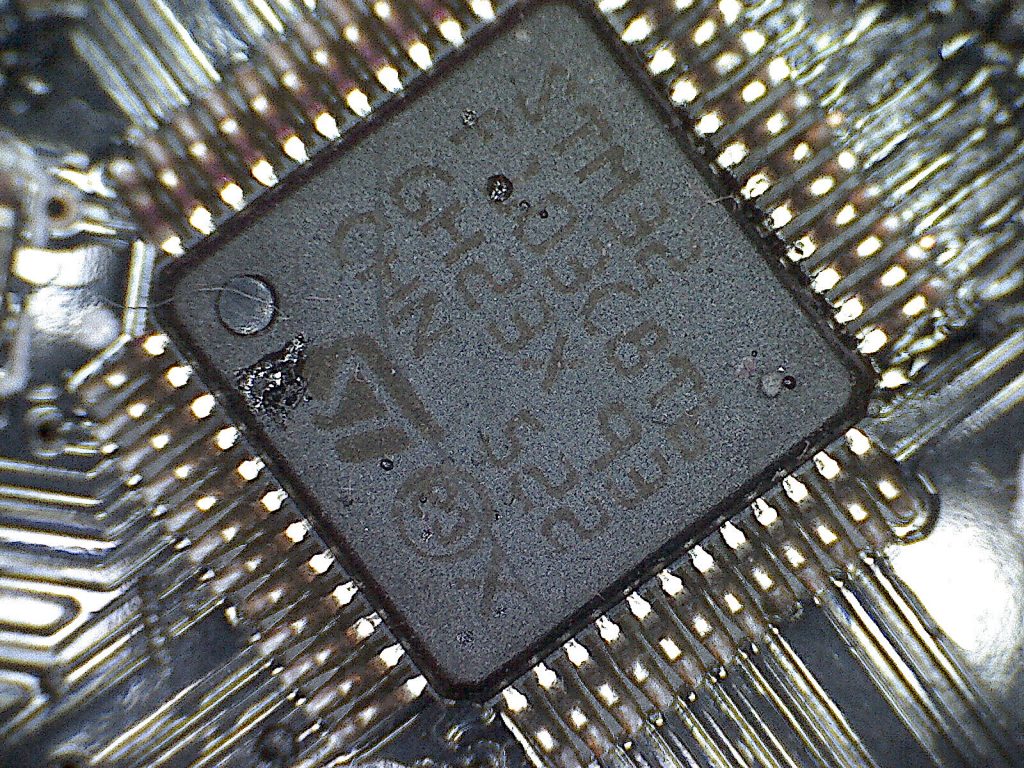

First, the chip from a “Black Pill†board bought recently:

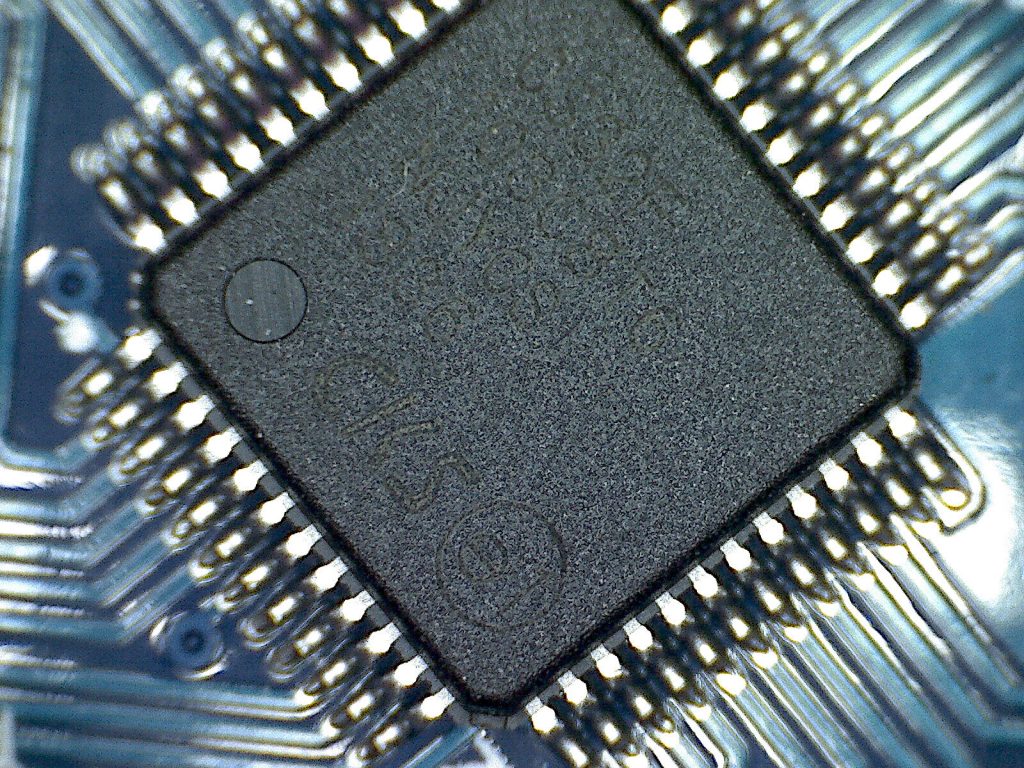

flux blobs aside, this is clearly marked STM32 F103C8T6 Compare with a “Blue Pill†bought last year:

the very tentatively marked CS32F 103C8T6 and its possibly fake CKS (“China Key Systemâ€) logo Knock-offs are rife in the cheap end of the market, and at least this chip is honest enough to say that it’s not from STMicroelectronics. While it may be possible to program these things with some heroic faffing about, consider balancing the effort required versus the time cost of doing so.

2: They may not have working USB

moar later (about the Blue Pill’s incorrect resistor)

3: The documentation is everywhere and nowhere and Google is not your friend

even moar later (about a very dedicated amateur’s hosting of the project documentation becoming too successful for him to afford)

(Huge thanks to Andrew Klaassen who provided me his notes for getting some of these boards at least able to run Blink under Linux.)

-

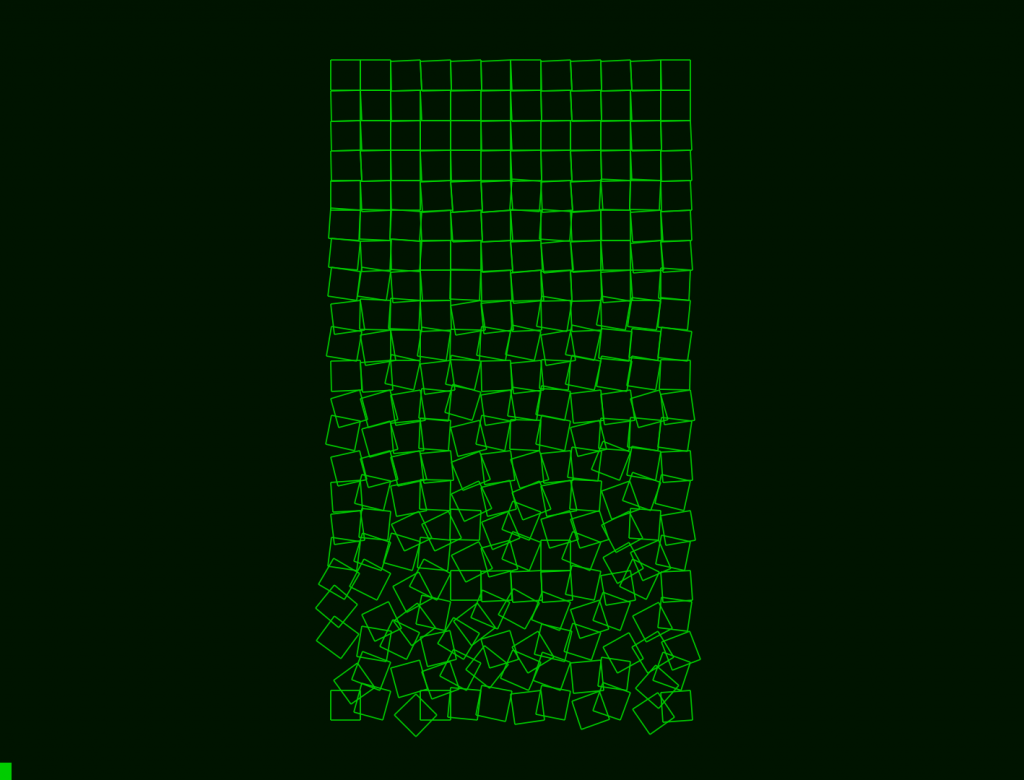

Schotter on a Tek 4010

Georg Nees’ Schotter, reproduced on a simulated Tek4010 display Georg Nees (1926–2016) was a pioneer of generative art. His piece “Schotter” (gravel) from 1968 displayed a rectangular array of squares with the position of each square becoming more random as the piece progressed.

The BASIC code for this video is based on Processing code by Jim Plaxco, http://www.artsnova.com/

The Tektronix 4010 display simulator is by Rene Richarz, https://github.com/rricharz/Tek4010

The BASIC interpreter with Tektronix graphics support is Matrix Brandy BASIC maintained by Michael McConnell, https://github.com/stardot/MatrixBrandy

(Higher-quality video at Georg Nees’ “Schotter”, reproduced on a simulated Tek4010 display at YouTube.)

100 REM Georg Nees "Schotter" reproduction - scruss, 2019-11 110 REM based on Processing 3 code by Jim Plaxco, www.artsnova.com 120 : 130 scrn_wd% = 2048: REM fixed screen size, unlike Processing 140 scrn_ht% = 1560 150 columns% = 12 160 rows% = 22 170 sqsize% = FN_min(scrn_wd% / (columns% + 4), scrn_ht% / (rows% + 4)) 180 padding% = 2 * sqsize% 190 randstep = 0.22 200 randsum = 0.0 210 randval = 0.0 220 dampen = 0.45 230 : 240 SYS "Brandy_TekEnabled", 1 250 A$=GET$: REM PLOT 4, 0, 0: PLOT 5, 0, 0 260 FOR y% = 1 TO rows% 270 randsum = randsum + (y% * randstep) 280 FOR x% = 1 TO columns% 290 randval = RND(1) * (2 * randsum) - randsum 300 PROC_square((scrn_wd% / 2) - (sqsize% * columns% / 2) + (x% * sqsize%) - (sqsize% / 2) + INT(randval * dampen), scrn_ht% - (padding% + (y% * sqsize%) - (sqsize% / 2) + INT(randval * dampen)), sqsize%, randval) 310 NEXT x% 320 NEXT y% 330 PLOT 4, 0, 0: PLOT 5, 0, 0 340 END 350 : 360 DEF PROC_square(cx%, cy%, side, angle) 370 LOCAL r, i%, pm% 380 pm% = 4: REM plot mode - move = 4, draw = 5 390 r = (side / 2) / (SQR(2) / 2) 400 FOR i% = 0 TO 4 410 PLOT pm%, cx% + r * COS(RAD(angle + i% * 90 + 45)), cy% + r * SIN(RAD(angle + i% * 90 + 45)) 420 pm% = 5 430 NEXT i% 440 ENDPROC 450 : 460 DEF FN_min(a%, b%) IF a% < b% THEN =a% ELSE =b%

Update: I get a mention here: Schotter – Georg Nees – Part 2!

-

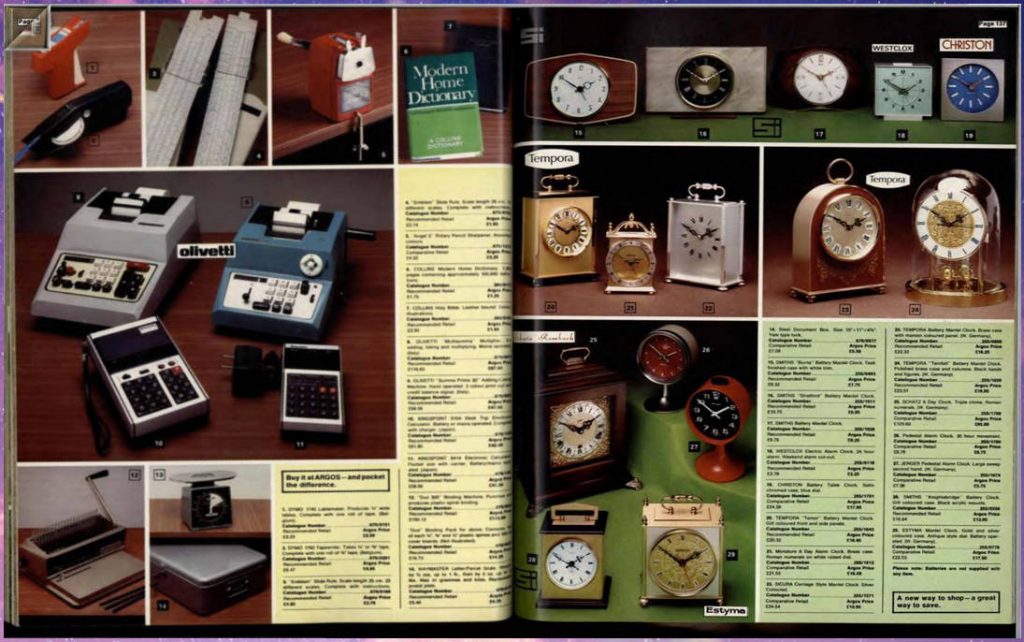

All of the Argos Catalogues

The 1974 Argos catalogue has slide rules … A little slice of UK consumer history: The Argos Book of Dreams, scanned Argos catalogues from 1974 to present. (Via b3ta)

It seems that all (?) of these are also up at the Internet Archive. They’re a little harder to find, and some don’t have previews. A decent search for one uploader’s history is “retromashâ€, though “argos catalogue†finds more. The Book of Dreams site seems only to have autumn/winter catalogues, while the Archive has the spring/summer ones too.

-

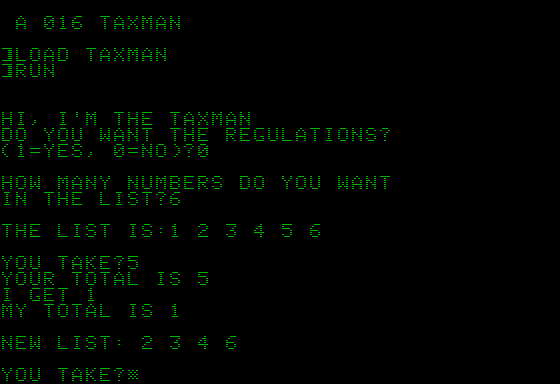

Taxman – a BASIC game from 1973

Back in 1973, the future definitely wasn’t equally distributed. While in Scotland we had power cuts, the looming three-day week and Miners’ Strike I, in California, the People’s Computer Company (PCC) was giving distributed computer access, teaching programming and publishing computer magazines. I don’t think we got that kind of access until (coincidentally) Miners’ Strike II a little over 10 years later.

flares? platforms? centre parting? bow tie? It was 1973 after all But the People’s Computer Company magazine archive is a sunny thing, overfilled with joyful amateur enthusiasm and thousands of lines of code fit to make Edsger Dijkstra explode. Of course it was written for the local few who had access to mainframes and terminals, but it hardly seems to come from the same world as the dark evenings in Scotland spent cursing the smug neighbours’ house with all the lights on, their diesel generator putt-putting into the night.

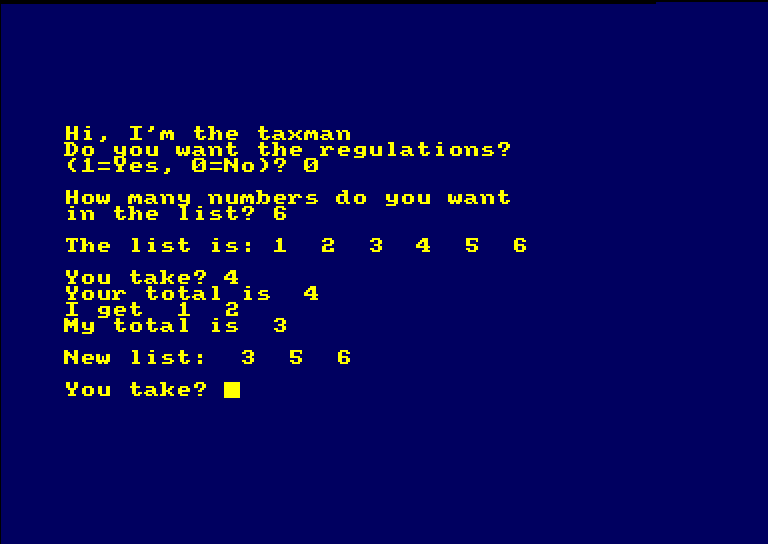

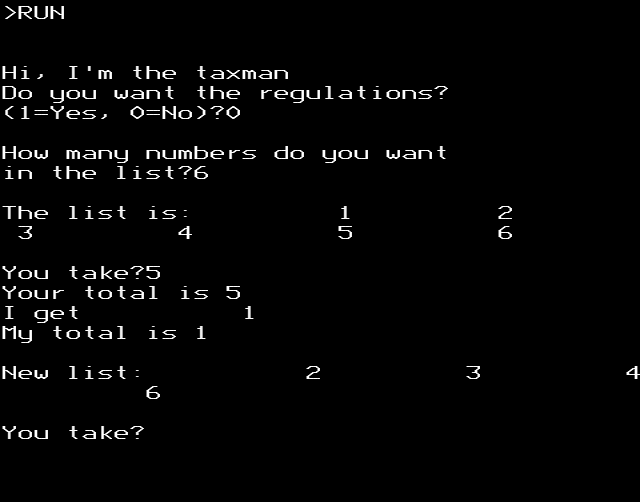

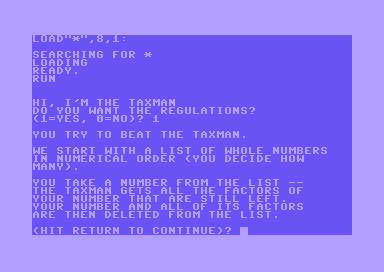

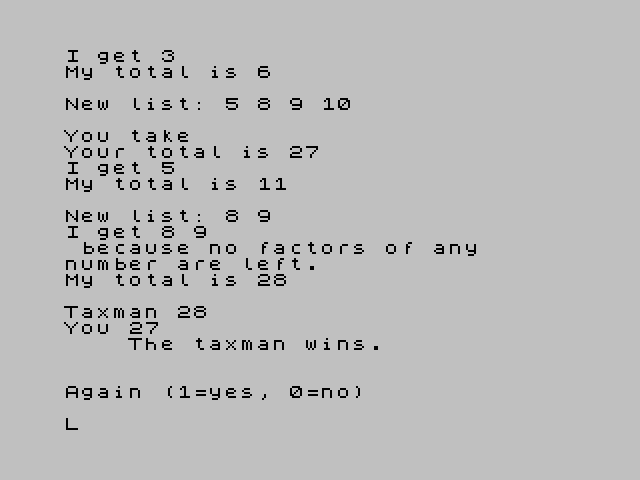

Lots of these games from the PCC era are forgettable now. The raw challenge of guessing a number on a text screen has paled somewhat in the face of 4K photo-realistic rendering. One game I found is still a little challenging, at least until you work out the trick of it: Taxman (or as the authors tried to rename it later, Factor Monster). Here’s a tiny sample game transcript:

Hi, I'm the taxman Do you want the regulations? (1=Yes, 0=No)? 0 How many numbers do you want in the list? 6 The list is: 1 2 3 4 5 6 You take? 5 Your total is 5 I get 1 My total is 1 New list: 2 3 4 6 You take? 6 Your total is 11 I get 2 3 My total is 6 New list: 4 I get 4 because no factors of any number are left. My total is 10 You 11 Taxman 10 You win !!! Again (1=yes, 0=no)?

Seems I sneaked a lucky win there, but it’s harder than it looks. The rules are simple:

- Start with a list of consecutive numbers

- You choose a number, but it has to have some factors in the list

- The taxman (or the factor monster, a concept I much prefer as it doesn’t reinforce the Helmsley Doctrine) takes all the remaining factors of your number from the list

- You get to choose a number from the list, which is now missing your previous choice and all of its factors, and repeat

- Once the list has no multiples of any other number, the taxman/FM takes the rest

- The winner is whoever has the largest sum.

For such a simple game (or perhaps, such a simple me) the computer wins surprisingly often. Since I find it fun to play, I thought I’d share the 1973 love as much as possible by porting to all of the BASIC dialects that I knew.

Plain text BASIC – taxman.bas – runs under interpreters such as bas. Almost verbatim from the 1973 publication. May not allow you to play again on some interpreters; you might want to try my slightly rearranged 40 column version that should run on systems that don’t allow a variable to be dimensioned twice.

taxman on Amstrad CPC: how BASIC programs look to me, yellow on blue 4 lyfe Amstrad CPC Locomotive BASIC – taxman.dsk – or as I call it, BASIC. 40 columns yellow on blue is how BASIC should look.

taxman on BBC, Mode 7: dig the weird spacing BBC BASIC – taxman.ssd – for all the boopBeep fans out there. You can actually play this one in your browser, too. Yes, the number formatting is weird, but BBC BASIC was always its own master.

taxman on C64 Commodore 64 – taxman.prg – very very upper case for this dinosaur of a BASIC.

taxman running on Apple II Apple II AppleSoft BASIC – TAXMAN.DSK – lots of fiddling with import tools and dialect weirdness because Apple.

taxman: end of game on ZX spectrum ZX Spectrum (Sinclair BASIC) – taxman.tap – 32 columns plus a very special dialect (no END, GOTO and GOSUB are GO TO and GO SUB) meant this took a while, but it was quite rewarding to get going.

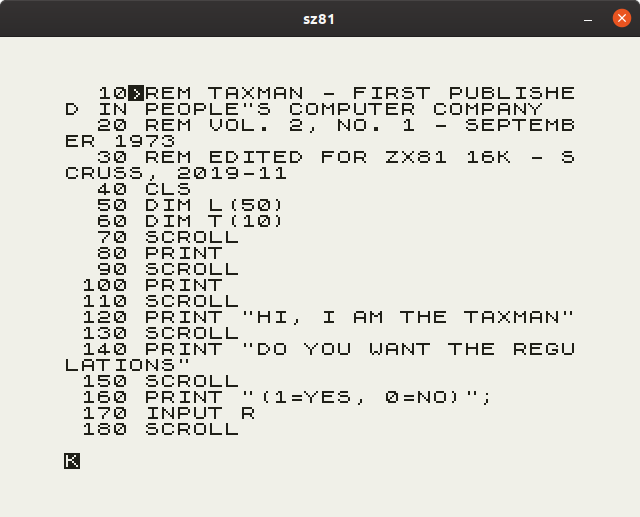

Taxman on ZX81: more SCROLLs than the Dead Sea Sinclair ZX81 (16 K) – taxman.p – this one was a fight. The ZX81 didn’t scroll automatically, so you have to invoke SCROLL before every newline-generating PRINT or else your program will stop. For some reason this version gets unbearably slow near the end of long games, but it does complete.