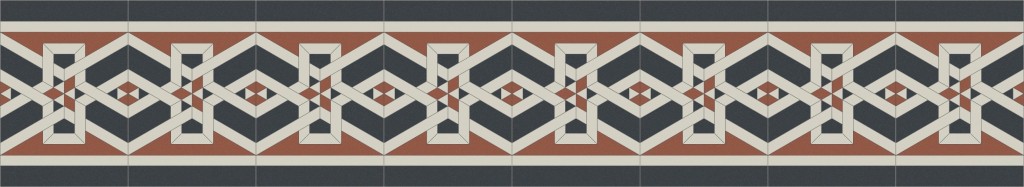

The little kite shape

fell out of an arch design I was studying, and I thought it was too nice to throw away. Must’ve been something about the falling leaves that made me choose colours like these.

Here’s the SVG, if you care to:

The little kite shape

fell out of an arch design I was studying, and I thought it was too nice to throw away. Must’ve been something about the falling leaves that made me choose colours like these.

Here’s the SVG, if you care to:

More tile work from the Aga Khan Museum’s fountain.

More tile work from the Aga Khan Museum’s fountain.

All I wanted to do was read a post on Winston Rowntree‘s Patreon page, yet something was blocked by uBlock Origin. In trying to find what it was, I found the page was pulling in 91 separate resources from 15 different sites:

s3.amazonaws.com s3-us-west-1.amazonaws.com api.amplitude.com maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com ajax.cdnjs.com cdnjs.cloudflare.com connect.facebook.net s-static.ak.facebook.com www.facebook.com www.google.com fonts.gstatic.com www.gstatic.com mandrillapp.com api.patreon.com www.patreon.com

Do we really need all that crud? It’s a bunch of trackers and fonts and mystery swf and javascript. It might be all responsive web like, but the more fancy you do, and the more of other people’s “TRUST ME†code you pull in, something’s gonna go wrong.

[gfycat data_id=”ImpeccableWiltedAfricanfisheagle” data_autoplay=true]

when the doge-hens invaded old london, take 2

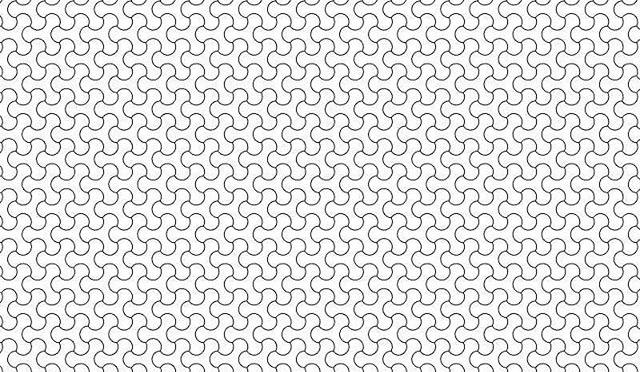

Just the output of a little PostScript program I wrote. Don’t let the little blobby shapes fool you; geometrically, they behave like hexagons. Yes, ½√3 figures a lot in the code.

svgo is, on the face of it, pretty neat: it takes those huge vector graphic files and squozes them down to something more acceptable. Unfortunately, though, the authors have seen too many files with junk machine-generated <metadata> sections, and decided that it’s all worthless.

Metadata isn’t junk; it’s provenance. Your RDF? Gone. Your diligently researched and carefully crafted Dublin Core entries? Blown away. The licence you agonized over? teh g0ne, man. svgo does this by default. It would be very easy to use this tool to take someone else’s graphic, strip out the ownership information, and claim it as your own. It would be wrong to do that, but the original creator would have to find your rip-off and go to the effort of challenging your use of it. All so much work, all so easily avoided.

You can make svgo do the right thing by calling it this way:

svgo --disable=removeMetadata -i infile.svg -o outfile.svg

There’s apparently a config option to make this permanent, but the combination of javascript, no docs and YAML brings me out in hives. Given that the metadata section of a complex file is typically a couple of percent of the total, it’s worth keeping. Software passes; but data lives forever, so be kind to it.